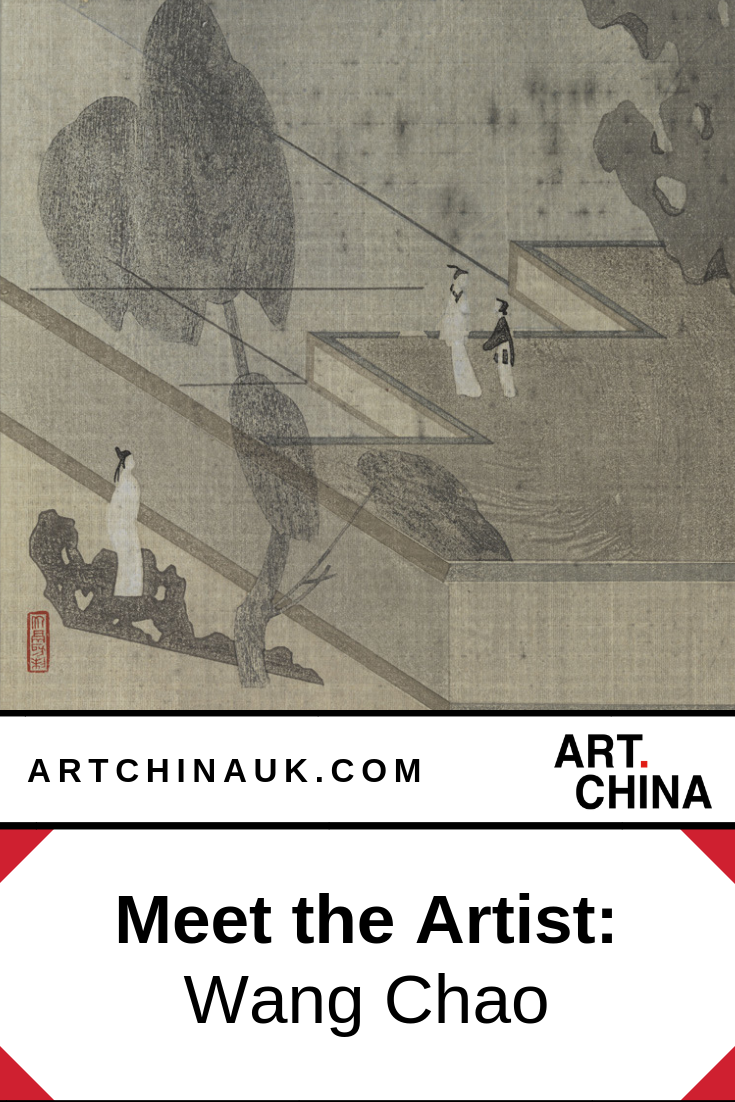

One of the more established Chinese artists we’ll be exhibiting at Asian Art in London at Design Centre Chelsea Harbour next month is Wang Chao, professor at the China Academy of Arts and director of its noted Purple Bamboo Studio. His work has been collected by leading museums in China, Europe and the USA.

Wang Chao makes multiple allusions to the past in both technique and in subject matter. The fine lines, refined colouring and subtle tonalities are reminiscent of illustrative printing from the Ming and Qing periods and Japanese Surimono. Of particular note in our collection are six prints based on art from around the time of Wanli, but the detail is simplified. The appearance is of aged silk paintings, achieved with the use of a newly manufactured paper called Tangzhi where we see the douban, multiple woodblock, method of printing.

But his work is best described by Dr. Anne Ferrer, Programme Director for the MA in East Asian Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. The remainder of this post is written in her words, an excerpt from an article titled “Continuity and Revival in Modern Chinese Culture: the Woodblock Prints of Wang Chao.”

“As a young artist establishing his career in the 1990s, Wang Chao has developed a type of individual antiquarianism in printmaking through which he uses formats, imagery, and techniques drawn from pre-modern China to offer a personal statement about the present. The character of this antiquarianism has evolved through his woodcuts which offers a significant and unusual achievement in the field of traditional art in contemporary China.

Wang Chao’s group of six prints (pictured above), produced in 2014 in the studios of the Xu Yuan 虚苑 printing workshops in Beijing, explore a new aspect of visual interpretation of Ming painting and book culture. The prints use subjects based on erotic imprints of the Wanli period, and illustrated editions of the Romance of the Western Chamber (Xixiang ji 西厢记). In Wang Chao’s reinterpretation of this subject matter, he simplifies the pictorial detail of landscape, architecture and textile patterning of late Ming book illustration, producing sparse compositions in the manner of sixteenth-century Wu School paintings. The prints define the architectural structures and garden ornaments with fine outline filled in with tones of monochrome, and the slight forms of the figures are printed in an overall tone of light ink, topped with darkly printed detail of hats and hair arrangements. Notable in these prints in Wang Chao’s representation of the materiality of aged silk paintings. The paper Wang Chao has uses for this set of prints is a newly manufactured paper called Tangzhi 唐纸 which is very thin and is so-named because its colour imitates Tang dynasty paper. In Wang Chao’s prints, the light olive tone of the paper gives the impression the colour of aged silk. Over the surface of the paper, Wang Chao prints a bamboo lattice in light monochrome to imitate the texture of woven silk. With the addition of dots and darker streaks of ink to show surface blemishes, representing the wear and tear in old silk paintings, each print presents a completely individual image. The printing process for each of these prints uses the douban method of printing, using between twenty-five and forty blocks made from both pearwood and plywood.

《传统饾版研习》”紫竹斋“传统木版水印实践与理论方向研究生,二年级,学生:王豫敏,导师:王超.jpg)

《传统饾版研习》”紫竹斋“传统木版水印实践与理论方向研究生,二年级,学生:黄剑波,导师:王超.jpg)

Wang Chao’s use of monochrome and subdued colours in his prints carries powerful artistic associations relating to the use of ink for expressive purposes in scholar-amateur painting. Many contemporary print-artists, following the revivalism of traditional painting, have produced largely monochrome prints with landscape and subjects such prunus, lotus, grasses and insects, in compositions which resonate with painting traditions of pre-modern China. These print-artists have been experimental in their use of materials and techniques, borrowing and adapting elements from both traditional and western-derived traditions to achieve a variety of different effects. Although Wang Chao is part of this group of print-artists, he occupies a separate category of his own in his use of techniques of colour printing associated with the Purple Bamboo Studio, and pictorial formats and subject-matter which are derived from late Ming printing.

Wang Chao is unique as a print-artist in contemporary China in his use of the douban printing technique in an unmodified form. His prints involve the use of multiple small woodblocks made from pearwood, each representing linear elements and intricate areas of colour, and blocks, often made from plywood faced with Manchurian ash giving a woodgrain texture, to build up larger areas of tone in the print. These blocks are printed in sequence, on a traditional Chinese printing table which achieves completely accurate registration. The embossing process used in the printed book Foreign Images is part of the colour-printing process and is carried out after the printing of ink and colour. It is achieved by placing the paper over an intaglio block which is rubbed with a wooden burnisher. Using this complex process involved Wang Chao in cutting more than forty individual blocks for the print Reminiscence, and twenty-three blocks for The Desk in the Jiuli Studio. Although Wang Chao is the only academy artist using the douban technique in a largely unchanged form in China, other artists frequently use the less technically demanding approach of colour printing using a set of blocks sharing the same register (taoban), in combination with other aspects of traditional or western realist printmaking.

Wang Chao’s woodblock prints investigate and rework different aspects of technique and subject matter in the printmaking history of pre-modern China. His prints are an important example of how the reworking of past models continues to be a powerful force in the generation of the highest quality traditional art in the twenty-first century.”

(The text above is from the article: Dr. Anne Farrer, “Continuity and Revival in Modern Chinese Culture: the Woodblock Prints of Wang Chao,” in Megan Aldrich and Robert J. Wallis eds., Antiquaries & Archaists: the Past in the Past, the Past in the Present (Reading, UK: Spire Books Ltd 2009), pp. 122-140, 162-167.)