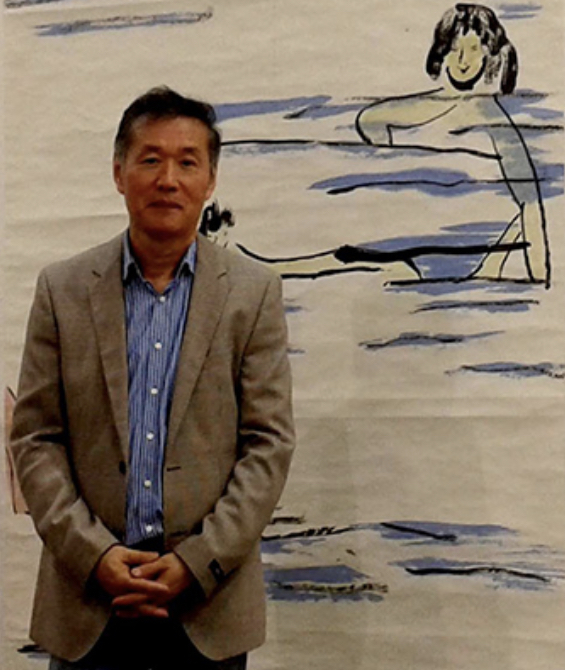

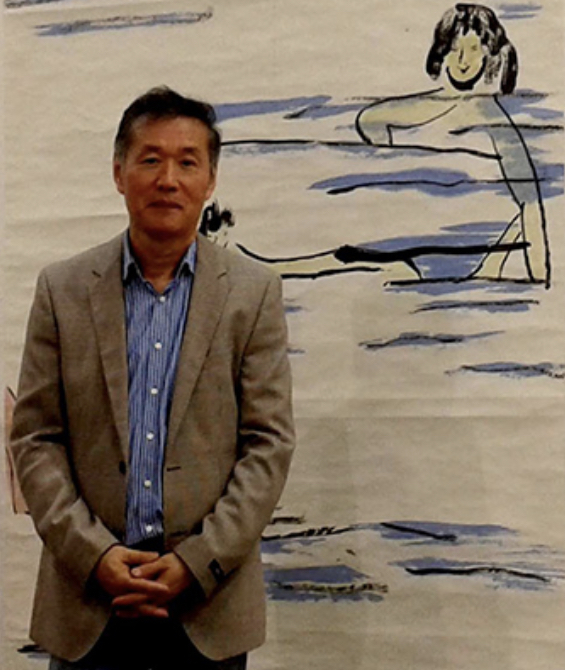

杨起艺术生涯自述

YANG QI’S BIOGRAPHY OF ART LIFE

我出生在一个艺术氛围浓郁的家庭,我父亲于二十世纪三十年代末毕业于当今中国最高艺术学府“中国美术学院”的前身之一“苏州艺术专科学校”, “苏州艺术专科学校“是由中国现代著名画家,美术教育家颜文梁先生和当时留学法国的部分中国艺术家于二十世纪三十年代在苏州创办和主持的;随后我父亲继续在国画大师徐悲鸿主教的”中央大学“艺术系继续深造,通过不断地磨练和积累很快即成为当时中国南方颇有影响的画家和艺术理论教授。我母亲出生于德国的法兰克福,外祖父和外祖母皆是早年在德国求学的学子,取得博士学位后留在了当地行医,因此我从小也接收了部分西洋文化的教育。

I was born in an artist’s family. My father graduated, around the end of 1930s, from Suzhou Art Institute, one of the predecessor institutes that constituted the unsurpassed China Academy of Art today. Suzhou Art Institute was established in the 1930s by Mr. Yan Wenliang, a great modern painting master and educator, together with a group of Chinese artists who studied in French. Later, my father continued his study in the art department of Central University under Chinese painting master Xu Beihong’s education. After a long period of training and studying, my father soon became an influential artist and art professor in southern China. My mother was born in Frankfurt, Germany; my grandparents went to Germany at a young age to study. They lived there as doctors after getting their PhDs. So I also attained a bit of Western education as a child.

我儿时的记忆中每当父亲作画时我和我哥哥、弟弟经常都会在一旁饶有兴趣的看着,或者我们兄弟三人也会学着父亲的样子拿出纸和笔信手涂鸦,我父亲也就时常给我们一些简单的指导,同时还给我们讲一些中国传统诗文和外国的艺术故事,在这种看似无心的潜移默化过程中,我最早的绘画情趣得以培养,印象中从我的孩提时代一直到青少年时代都是跟父亲在一起画,而且学习素描、雕塑、绘画都是自然而然的同时发展起来的,很显然我父亲就是我的艺术启蒙 老师。

In my early memories, in great interest, my brothers and I often watched my father painting. Sometimes we also made casual drawings mimicking our father’s work. He often gave us some lessons, telling us stories of traditional Chinese poetry and foreign arts. Unconsciously influenced by this creative atmosphere, my original interest in painting developed. I spent my childhood and teenage years painting with my father, discovering initially how to sketch, sculpt and paint spontaneously around the same period. Apparently, my father was my first teacher of the arts.

对我产生过影响的艺术家在不同时期有好几位,几乎都是国外的艺术家,中国的艺术家里面只有一个,那就是中国现代画家,散文家,美术教育家丰子恺。小的时候我们经常在我父亲那受到一些影响,也看过的丰子恺的一些中国抗战时期的书本插图,画了一些非常有人情味的生活的一些场景,一些绘画还配有诗文,记忆非常深刻。国外艺术家比较早的有毕加索,夏加尔。尤其我来的欧洲以后,首先是德国的表现主义一直到现在的新表现主义对我影响巨大,使我从一个中国的艺术家来到德国以后最后变成德国的新表现主义的艺术家代表人物之一,这是一个非常重要的过程。

I was influenced by different artists during different times, most of whom were Western artists. The one and only Chinese artist who influenced me greatly was Feng Zikai, a famous modern painter, prose writer and art educator. Influenced by my father during childhood, I have also seen many paintings in Feng Zikai’s books created during the War of Resistance Against Japan. Those empathetic images of life scenes, and the poems written with the paintings, rooted themselves deeply in my mind for a long time. Foreign artists such as Picasso and Chagall influenced me significantly; living in Europe, German expressionism and later neo-expressionism both transformed me from a Chinese artist into a representative figure of German neo-expressionism, which has been an important process for my art.

我的装置很大程度上都是来自于哲学,中国和德国的哲学。比方说中国的道家的哲学和德国的哲学家海德格对我的影响很大,还有艺术上面就是德国的Joseph Beuys。在我刚到德国来的时候,我对他的作品非常感兴趣。

My work, to a large extent, is based on Chinese and German philosophies, such as Taoism, as well as Heidegger’s theories. In terms of arts, German artist Joseph Beuys raised my interest greatly when I first came to Germany.

我不大喜欢波普艺术,我是比较钻牛角间的。对学术性的艺术我是非常感兴趣,我本人一直投身于学术艺术方面的一些创造和发展。

I don’t favour pop art much as I am more into academic art. I have spent a long time developing and creating art with an academic focus.

在个人生活中哪些发生过事情对我的创作影响很大,第一件重要事情就是我走出了国门来到了德国,看到了一些我曾经在艺术杂志上见过的一些非常宏伟的作品。从古典主义,从文艺复兴以前,从中世纪一直到现当代的艺术作品,很多大师的原著我都如饥似渴的去看,去注意研究和对比,因为我一直想我能够超越他们吗?同时也看到了很多欧洲美术馆这大量艺术家的原作,包括我不曾了解的一些艺术家。

There are a few things in life that have influenced my art. The first thing was coming to Germany to see great masterpieces in person that I had previously seen in magazines. From classicism to renaissance, from medieval arts to modern and contemporary ages, I ventured among as many masterpieces as I could. With a great dedication of time and interest, I studied and compared their works, contemplating how my own art could reach and exceed their accomplishments. I also have seen many original artworks by European artists in galleries, including some artists I didn’t know.

这个过程是个非常重要的转折点,我一直在思考:如果这个世界上已经有这么多人画过这么多画的话,那么我如果再继续的画,我就不能够再和他们一样的画,我就要搞出自己的东西。所以整个一个人从中国到了德国从东方来到西方,这个艺术观念的转变是在设身处地的环境中才能产生的。在欧洲在西方,特别是在德国这个当代艺术发展的特别旺盛和迅猛的一个时期,那个时期是从八十年代末到九十年代对我来说非常重要。

The above experience was an important transformational point in the way I think about the arts: there have been so many people in the world creating different artworks that I should continue my path creating something different from existing forms; I should create something of my own. Moving from China to Germany, from an Eastern world to the West meant my entire artistic insight has transformed within a complete change of environment. In the West, especially in Germany during the late 80s and 90s which was its rapid flourishing period of contemporary art, I attained great knowledge of the arts.

第二件重要事情就是我从抽象进入了人物。我从中国出来时候因为想把哲学把禅宗、道家,把西方德国的辩正主义哲学结合到我的艺术里面,我自己一直在思考,我怎么样画画。因此我开始琢磨自己的感觉,我想改变我自己的风格,所以那个时候我画抽象。九十年代末的时候,那个时候在德国及欧洲的一些大型美术馆和中国有我做过很多大型的展览后来突然觉得我可以改变了,我从抽象再回到我的人物表现的时候,那个时候我的创作非常的自由,非常的狂放。

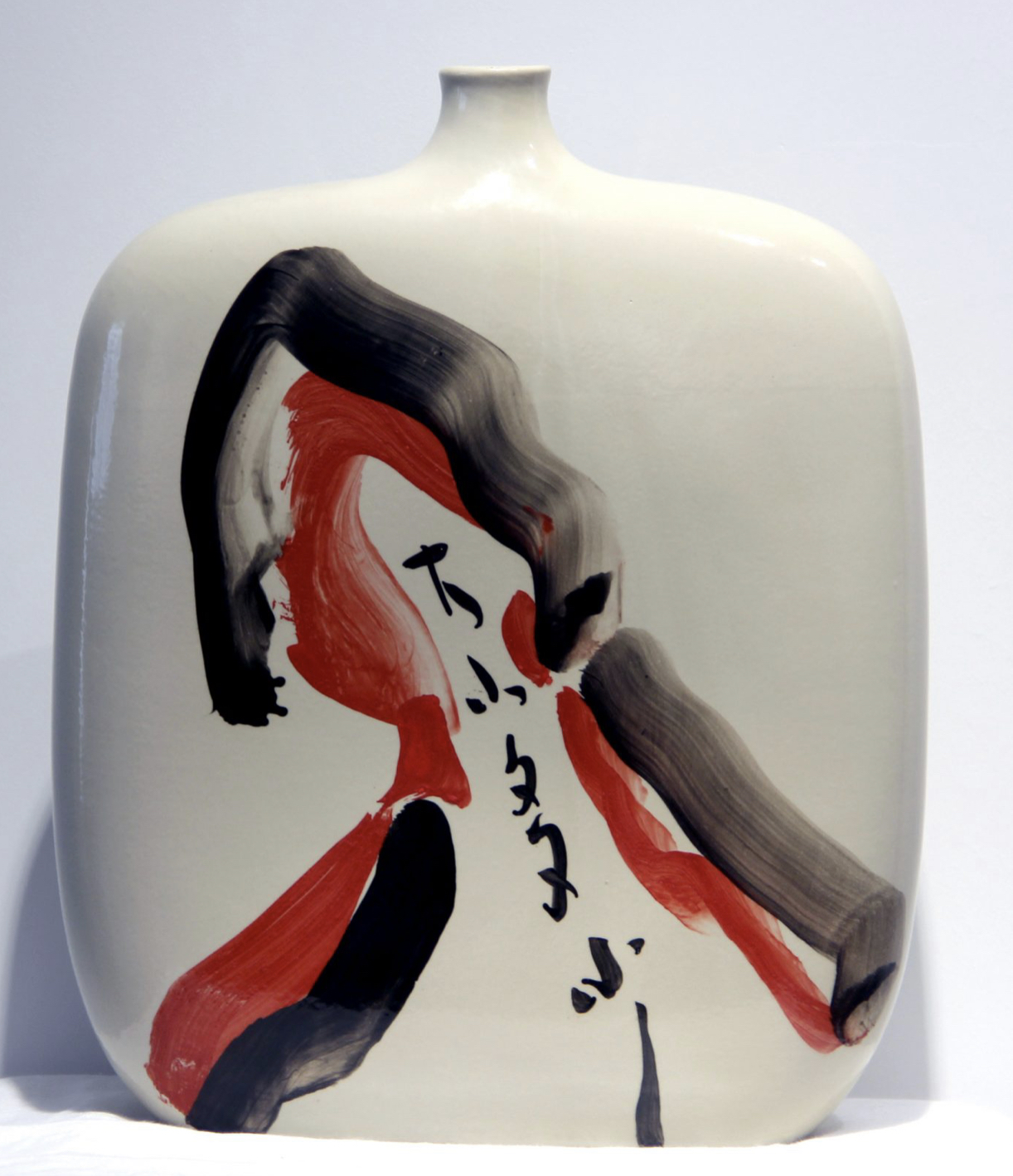

The second major point was my shift from abstract art to figurative art. I have always longed to fuse Zen, Taoism and German dialecticism into my artwork. I had been thinking about the way I paint, the feelings I have when I paint and the changing of my style, so I did abstract paintings. At the end of 90s, after being exhibited in many major art museums in China and Germany, I felt that it was time for a change. Thus, my art-making became very free and wild when I changed from abstract to figurative work.

新表现主义对我的影响,从把自己完全的解放,抽象的解放,最后又回到一个抽象的人物,这是个非常重要的一个事情,那个时候在九十年代末就慢慢地开始从全抽象就又回到学院派技术的人物上。后来我觉得我自己的作品开始有所不同,我就可以更加自信地把自己的感觉放进去,把自己的情操放进去,因此自己的风格也逐渐形成。因此在那个时候就慢慢地有欧洲艺术评论家称我是九十年代末在德国是一个小有名气的,拥有个人风格的抽象画新表现主义的一个艺术家。

Neo-expressionism has influenced me, freeing me from abstraction and leading me back to figurative painting. It has become a significant part of my art. I gradually changed from pure abstract style to figurative painting, incorporating academic techniques from the late 90s. Later, I noticed that my works appeared differently, meaning my own style was established confidently with more feelings and emotions added in. It was in the late 1990s in Germany when some European critics called me a “rising neo-expressionist in abstract art with unique style”.

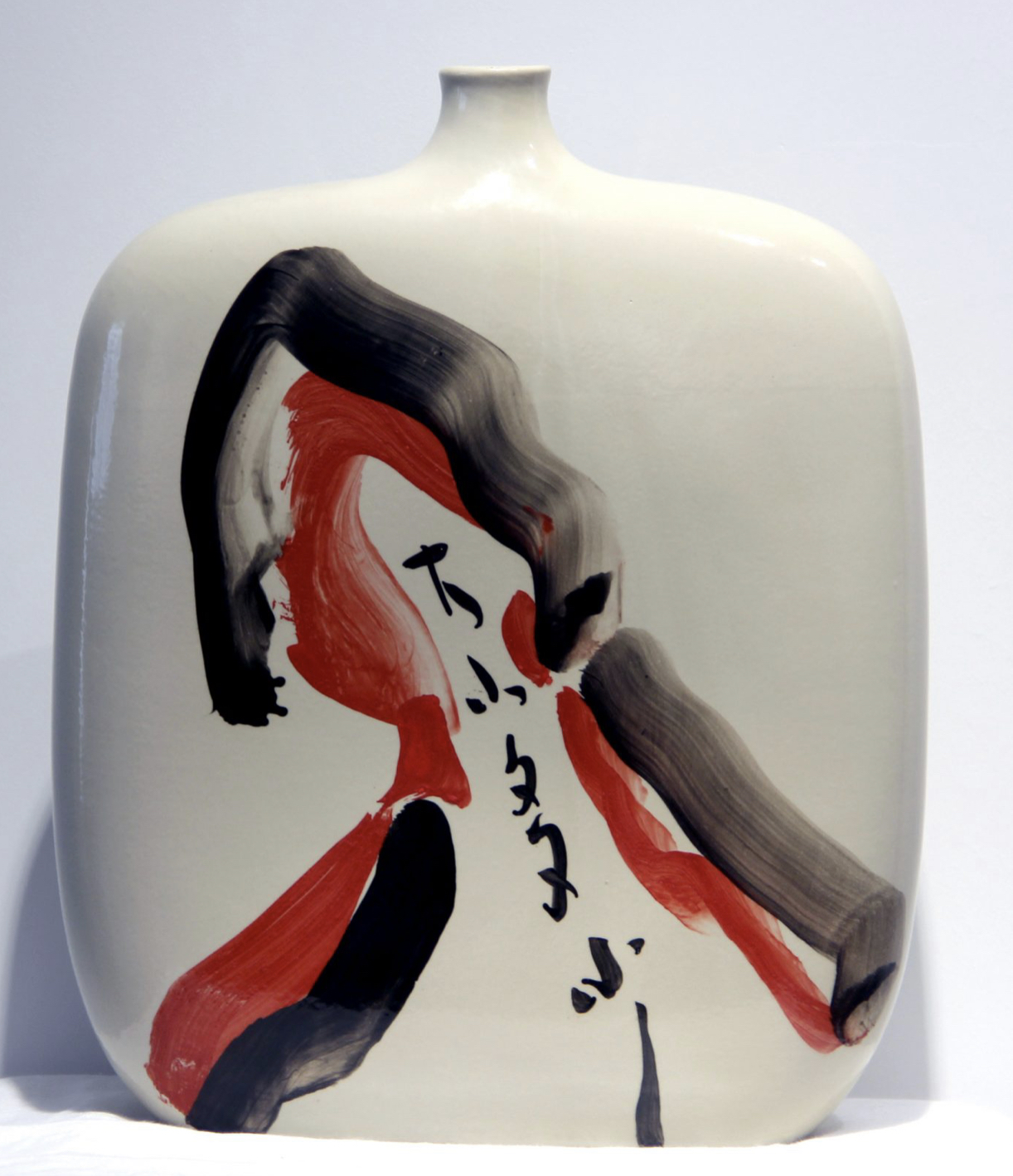

第三件重要事情就是我有一个非常长的一个做装置的时期,我从九十年代末一直到今天随着我的绘画我都一直在做我的装置。我参加很多重要的展览也都有的绘画也有我的装置包括的个人的展览。所以我的装置,在某种意义上也突出的代表了我的风格。一个艺术家,一个画家,他不仅绘画,它从各方面多元素的表现自己的风格,用各种不同的艺术语言去反映自己的整体的面貌。当今世界很多知名的艺术家。他们都不仅在绘画,不仅做雕塑,他们都拥有一个多元的艺术表现方式,因为艺术发展的二十一世纪以后人进入一个非常集中的,一个非常类型的一个时代。所以这个类型的时代促使了我完全的投入这个造型和表现,造型就是除了绘画还有装置。那除了装置还有摄影啊,还有多媒体等等。这些各个方面都形成了我作为在当今二十一世纪的一个艺术表现的全部含义,所以我觉得成为一个艺术家。他是要经过许许多多的过程,这个锤炼的过程就是一个自己革命的过程,一个自我反省的过程。

The third important thing was my long working period during which I made art installations. This started from the late 90s alongside my paintings and continues today. I participated in many art exhibition with both my paintings and installations, from group shows to solo shows. Those installations stand for my own style to a major extent. An artist should not only do paintings, but also should use various artistic elements to express his styles, showing a comprehensive artistic consideration with diversified art languages. Many famous artists today use diverse artistic media, varying from paintings to sculptures and to a wider range of styles. Art develops into an intensively diversified portfolio of forms. This has encouraged me to devote my time to creating paintings, installations, photography and multi-media arts, which all formed my contemporary artistic expression in the 21st century as a whole. I think, as an artist, the process of changing and transforming artistic styles is also a process of self-revolution and self-introspection.

第四个重要事情就是我成为德国新表现主义艺术家以后把我自己的个人的艺术水准推到一个非常重要的一个高度,从2002年至今十五年的时间里,我参加了很多国际上的有非常重量级的艺术展览,我作为一个代表性艺术家能加入了这个行列对我个人来说是个非常重要的一个鼓励。我作为一个艺术家能够在西方能够在德国站住脚,而且能够把自己风格能够宣传和表现出去。所以这是个非常非常重要的一个阶段,这个感觉对我来说非常重要。因为这个感觉就更加的自信。作为一个艺术家就是要自信,必须要骄傲,否则这个人的艺术就非常非常的胆怯,所以通过把自己这个推出去,把自己能够放到一个比较高的位置上去。就能够跟国际上的艺术家比肩,做一些国际性的重要的展览。这都是非常非常重要的,对于任何一个艺术家来说,这都是一个鞭策。

The forth important thing has been to raise the quality of my art to new heights after being declared a German neo-expressionist. For fifteen years since 2002, I have participated in many major art exhibitions throughout the world, which has been a great encouragement for me to continue creating art. Being a recognized artist in the West, I am able to promote and express my own art style. This experience has been exceptional to me, giving me great confidence in my artistic life. An artist is meant to be confident and proud, otherwise his art will show timidity. I was able to advocate for myself and push my art to a higher level, to be compared with international artists and to join important exhibitions, which would be hugely encouraging for any artist.

我离开中国三十年了,所以中国发生什么事情我就像一个外国人一样去听一听看一看,看看媒体如何报道,我也从来不打关心政治,所以这些重要大事对我来说没有什么关系。

I left China thirty years ago, thus I always look at issues happening in China with a foreigner’s perspective. Looking at the media’s presentations, I don’t really care about politics; those major political issues seem irrelevant to me.

在欧洲或者世界上其它地方发生的事情,即便是一个社会发展潮流。一个艺术家他始终是站在自己的角度和立场来看待这个世界,他不会为这个世界发生一些左右,除非是一个战争或者类似事件。我认为在欧洲这么和平的环境下,尽管有这样那样的事情,但是老百姓的生活和整个欧洲社会和文化的大环境,一个包括文化和修养的机遇,对于一个艺术家的发展没有很大的干扰。

Issues in Europe or other parts of the world, or even social development topics, are to an artist objective matters which he should be looking at with his own angle and position. He should not be swayed by the issues, unless there are wars or similar chaos. I think in a peaceful environment in Europe, people’s life and society, as well as the broader culture and cultivation opportunities are not vastly influential in an artist’s development.

最后这个问题我为什么选择我当前的手法这个问题提出的有点荒谬,一个艺术家的成功,他不是选择这种艺术手法。是这个艺术这个风格在经过一个艺术家一生的一个锤炼以后。他产生了这个艺术风格,不是说我选择了这个风格去做我的艺术。我表现我的艺术是用我的心灵,用我的血肉。用我的精神用我的个人的整体的灵魂去表现这个艺术的。所以这和一个艺术家他的独立性是有关系的,因为任何艺术家他都不需要听别人去说,你应该怎么他应该怎么。一个艺术家的本体,他是一个世界,他是个独立的世界,这个世界要去影响更多的世界。这个独立的世界是最重要的,所以我不需要去选择什么我就做我想做的,这个就是我的艺术的立场。

Any interview question asking about my choice of style and technique appears a bit absurd. A successful artist does not choose his style or technique, but forms the style after a life-long exploration of his artistic development. He forms this style, instead of choosing it, to create art. I express my art with heart and flesh, with my spirit and whole soul. It’s a matter of independence for an artist; he needs not to listen to others’ opinions. An artist is in a world of his own, thus he could influence the outside world as a whole. I have not chosen a style.

这个采访不是在作秀采访就是要说真话,就是向新闻媒体是说出一个艺术家的他想说的事情,其他都不是我的事情。因为我只对我自己负责,我对我的艺术负责,这个至于别人去怎么样欣赏我的艺术去夸奖我的艺术或者去批评我的艺术,这都是很自然的事情。

This interview should not be a show, thus I want to express what is true to me, saying what I want to say to the media. Other things are not related to me. I am responsible to my own art, and to myself. How people praise or criticise my art should be a very natural thing.

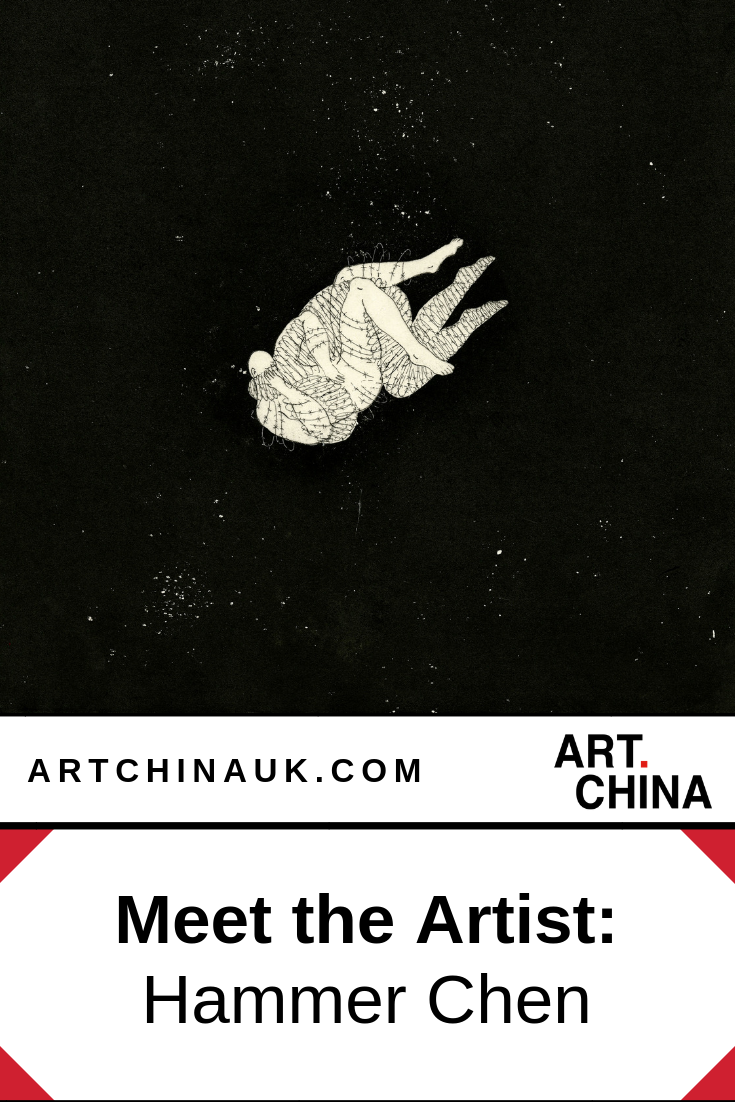

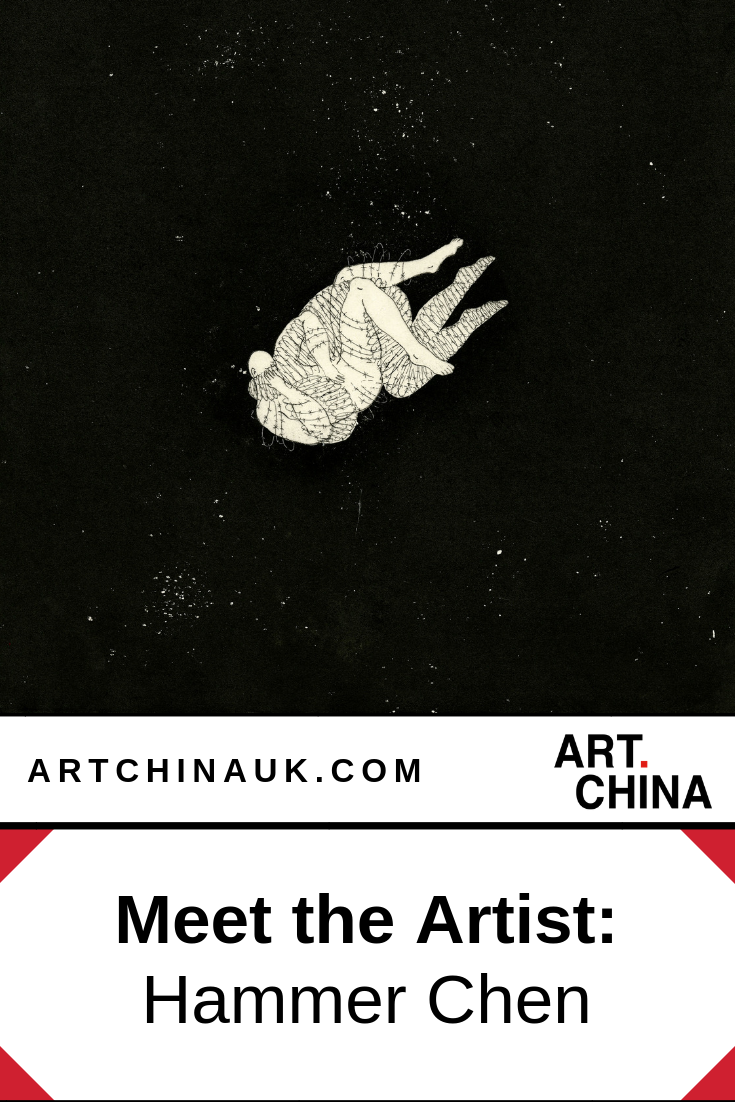

One of the talented emerging Chinese artists we’ll be exhibiting at November’s Asian Art in London show is Hammer Chen, whose creative life bounces between Shanghai and London. Hammer is a printmaker, an artist and illustrator whose work, as she puts it, stems from an interest in using marks and textures to express sensations and emotions. Since 2013, she has had several exhibitions in London and, in 2016, graduated with an MA in Illustration from Camberwell College of Arts. She won the Gwen May Award from the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers (RE) in 2016 as well and was selected to be a member artist of the RE in the same year.

From 2016, Hammer began to run a printmaking art studio called Wait and Roll in Shanghai in an effort to increase access to printmaking in China. Services of her studio include printmaking workshops, printmaking publication, print service, open space and an artist residency. The photos throughout this post were all taken at Wait and Roll.

Hammer’s series of prints that we’ll have on display in the ArtChina booth at Asian Art in London is from her degree project.They’re much darker than the work in the images here, and run deep into the psychology of being. They revolve around the topic of Maladaptive Daydreaming, which she defines in our interview below. Read on to find out more.

ARTCHINA UK: Tell us about the work you made for your MA project.

HAMMER CHEN: My subject is Maladaptive Daydreaming. “Maladaptive daydreaming is a psychological concept to describe an extensive fantasy activity that replaces human interaction and interferes with academic, interpersonal, or vocational functioning.” So the series of works is exploring fantasy, struggle, disconnect between mind, body and self.

ARTCHINA UK: What inspired you to make your final piece?

HAMMER CHEN: The main reason that I chose the subject is that I realised I’ve developed Maladaptive Daydreaming in the last two years and therefore felt the need to explore this in my work. Also, I realised lots of people are suffering from this but they don’t want to share the bad experience of daydreaming because they are afraid of incomprehension. I do feel it’s necessary to let people know that this problem exists and we should pay attention to it.

ARTCHINA UK: How did you start this project? If you’d like you can make it as a step by step explanation.

HAMMER CHEN: I recalled a lot my previous experience to begin the sketches. It was hard in the beginning, but after I started to open myself up and express my real feelings, it became a process of self-curing. I made many sketches before I began etching. Even while I was in the etching stage, I still kept doing sketches. I picked the ideas which are most expressive then made them into etching pieces.

ARTCHINA UK: What technique did you choose to make your final piece and why?

HAMMER CHEN: I chose to do etching for the final project. Before I started printmaking, my works went through several different stages. They pretty much all stemmed from my interest in making marks and textures.The reason I am so keen on working with textures is that they can give an image a strong atmosphere, provide a different quality and build space for sensations and for the imagination to run wild. When I got into the printmaking studio, I realised that this is an ideal way to produce works with great quality which, at same time, can still be narrative.

ARTCHINA UK: Tell us about any difficulties or challenges you found while making your final piece.

HAMMER CHEN: The challenge might be the uncertainty of the final results and the long process. Sometimes you won’t know what is going to happen on your plate until the last minutes before you see the prints. But actually, I really enjoyed the waiting and appreciated all the failures and surprises that happened in my works throughout the process.

To see Hammer’s work in person, visit the ArtChina booth at the upcoming Asian Art in London exhibition or the Woolwich Contemporary Art Fair, both in November 2018, where we will have her prints on display and for sale.

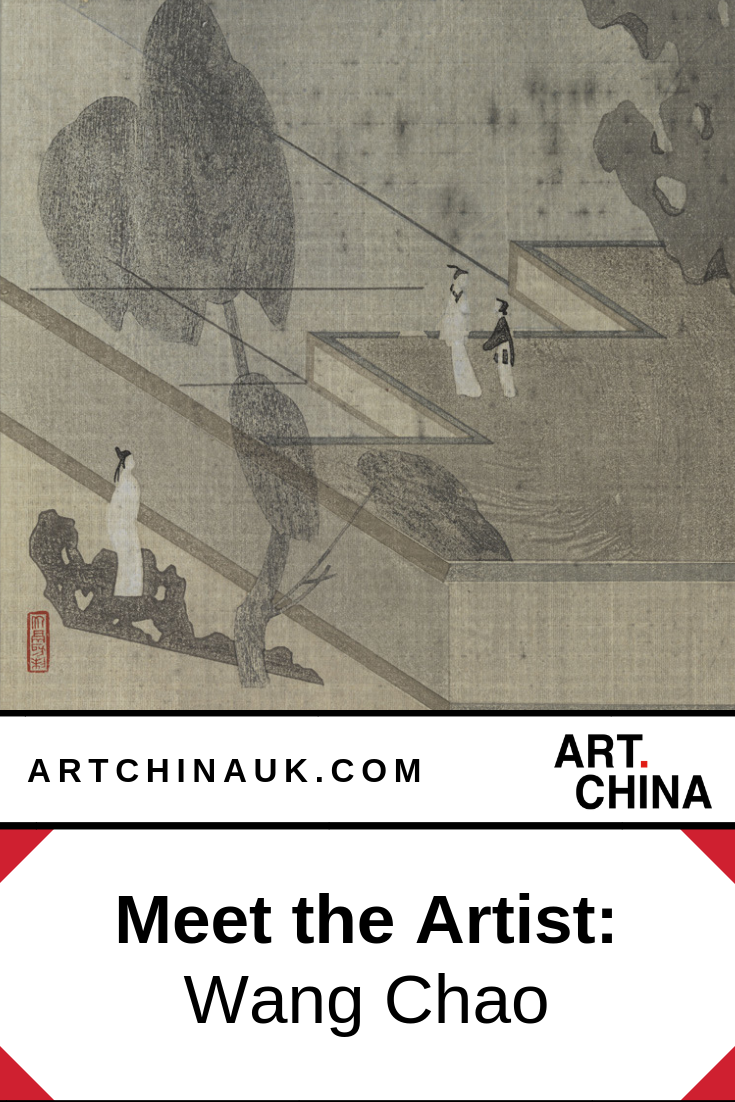

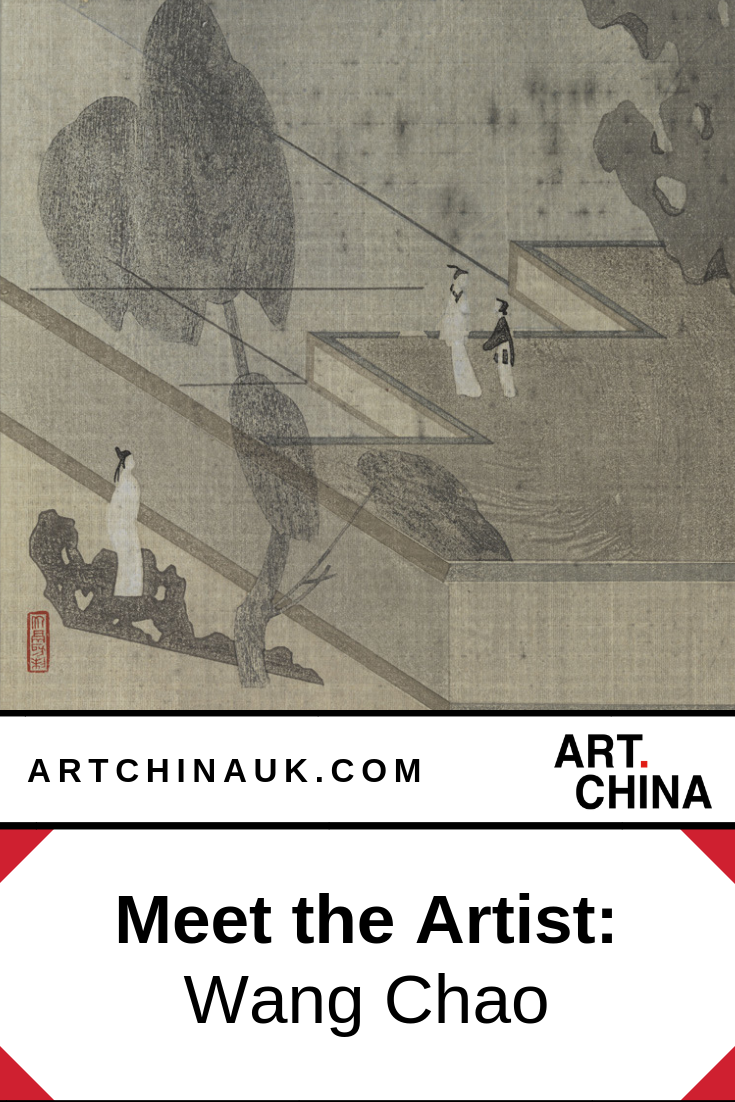

One of the more established Chinese artists we’ll be exhibiting at Asian Art in London at Design Centre Chelsea Harbour next month is Wang Chao, professor at the China Academy of Arts and director of its noted Purple Bamboo Studio. His work has been collected by leading museums in China, Europe and the USA.

Wang Chao makes multiple allusions to the past in both technique and in subject matter. The fine lines, refined colouring and subtle tonalities are reminiscent of illustrative printing from the Ming and Qing periods and Japanese Surimono. Of particular note in our collection are six prints based on art from around the time of Wanli, but the detail is simplified. The appearance is of aged silk paintings, achieved with the use of a newly manufactured paper called Tangzhi where we see the douban, multiple woodblock, method of printing.

But his work is best described by Dr. Anne Ferrer, Programme Director for the MA in East Asian Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. The remainder of this post is written in her words, an excerpt from an article titled “Continuity and Revival in Modern Chinese Culture: the Woodblock Prints of Wang Chao.”

“As a young artist establishing his career in the 1990s, Wang Chao has developed a type of individual antiquarianism in printmaking through which he uses formats, imagery, and techniques drawn from pre-modern China to offer a personal statement about the present. The character of this antiquarianism has evolved through his woodcuts which offers a significant and unusual achievement in the field of traditional art in contemporary China.

Wang Chao’s group of six prints (pictured above), produced in 2014 in the studios of the Xu Yuan 虚苑 printing workshops in Beijing, explore a new aspect of visual interpretation of Ming painting and book culture. The prints use subjects based on erotic imprints of the Wanli period, and illustrated editions of the Romance of the Western Chamber (Xixiang ji 西厢记). In Wang Chao’s reinterpretation of this subject matter, he simplifies the pictorial detail of landscape, architecture and textile patterning of late Ming book illustration, producing sparse compositions in the manner of sixteenth-century Wu School paintings. The prints define the architectural structures and garden ornaments with fine outline filled in with tones of monochrome, and the slight forms of the figures are printed in an overall tone of light ink, topped with darkly printed detail of hats and hair arrangements. Notable in these prints in Wang Chao’s representation of the materiality of aged silk paintings. The paper Wang Chao has uses for this set of prints is a newly manufactured paper called Tangzhi 唐纸 which is very thin and is so-named because its colour imitates Tang dynasty paper. In Wang Chao’s prints, the light olive tone of the paper gives the impression the colour of aged silk. Over the surface of the paper, Wang Chao prints a bamboo lattice in light monochrome to imitate the texture of woven silk. With the addition of dots and darker streaks of ink to show surface blemishes, representing the wear and tear in old silk paintings, each print presents a completely individual image. The printing process for each of these prints uses the douban method of printing, using between twenty-five and forty blocks made from both pearwood and plywood.

《传统饾版研习》”紫竹斋“传统木版水印实践与理论方向研究生,二年级,学生:王豫敏,导师:王超.jpg)

《传统饾版研习》”紫竹斋“传统木版水印实践与理论方向研究生,二年级,学生:黄剑波,导师:王超.jpg)

Wang Chao’s use of monochrome and subdued colours in his prints carries powerful artistic associations relating to the use of ink for expressive purposes in scholar-amateur painting. Many contemporary print-artists, following the revivalism of traditional painting, have produced largely monochrome prints with landscape and subjects such prunus, lotus, grasses and insects, in compositions which resonate with painting traditions of pre-modern China. These print-artists have been experimental in their use of materials and techniques, borrowing and adapting elements from both traditional and western-derived traditions to achieve a variety of different effects. Although Wang Chao is part of this group of print-artists, he occupies a separate category of his own in his use of techniques of colour printing associated with the Purple Bamboo Studio, and pictorial formats and subject-matter which are derived from late Ming printing.

Wang Chao is unique as a print-artist in contemporary China in his use of the douban printing technique in an unmodified form. His prints involve the use of multiple small woodblocks made from pearwood, each representing linear elements and intricate areas of colour, and blocks, often made from plywood faced with Manchurian ash giving a woodgrain texture, to build up larger areas of tone in the print. These blocks are printed in sequence, on a traditional Chinese printing table which achieves completely accurate registration. The embossing process used in the printed book Foreign Images is part of the colour-printing process and is carried out after the printing of ink and colour. It is achieved by placing the paper over an intaglio block which is rubbed with a wooden burnisher. Using this complex process involved Wang Chao in cutting more than forty individual blocks for the print Reminiscence, and twenty-three blocks for The Desk in the Jiuli Studio. Although Wang Chao is the only academy artist using the douban technique in a largely unchanged form in China, other artists frequently use the less technically demanding approach of colour printing using a set of blocks sharing the same register (taoban), in combination with other aspects of traditional or western realist printmaking.

Wang Chao’s woodblock prints investigate and rework different aspects of technique and subject matter in the printmaking history of pre-modern China. His prints are an important example of how the reworking of past models continues to be a powerful force in the generation of the highest quality traditional art in the twenty-first century.”

(The text above is from the article: Dr. Anne Farrer, “Continuity and Revival in Modern Chinese Culture: the Woodblock Prints of Wang Chao,” in Megan Aldrich and Robert J. Wallis eds., Antiquaries & Archaists: the Past in the Past, the Past in the Present (Reading, UK: Spire Books Ltd 2009), pp. 122-140, 162-167.)

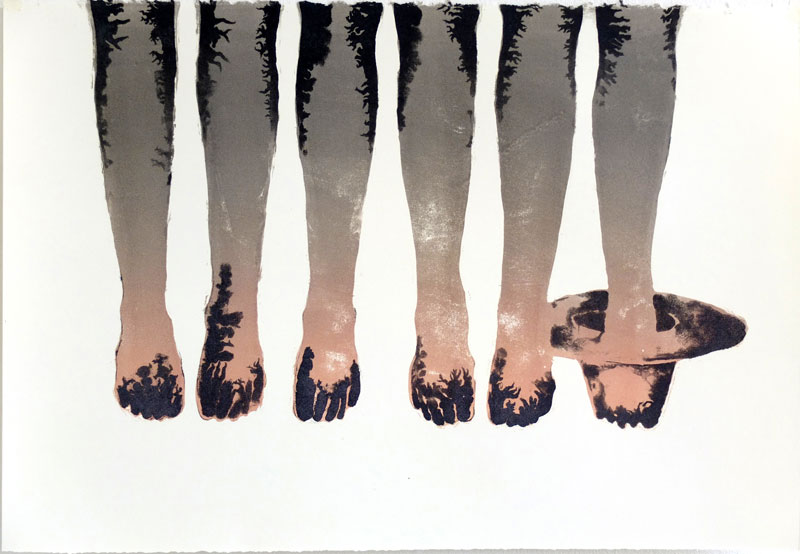

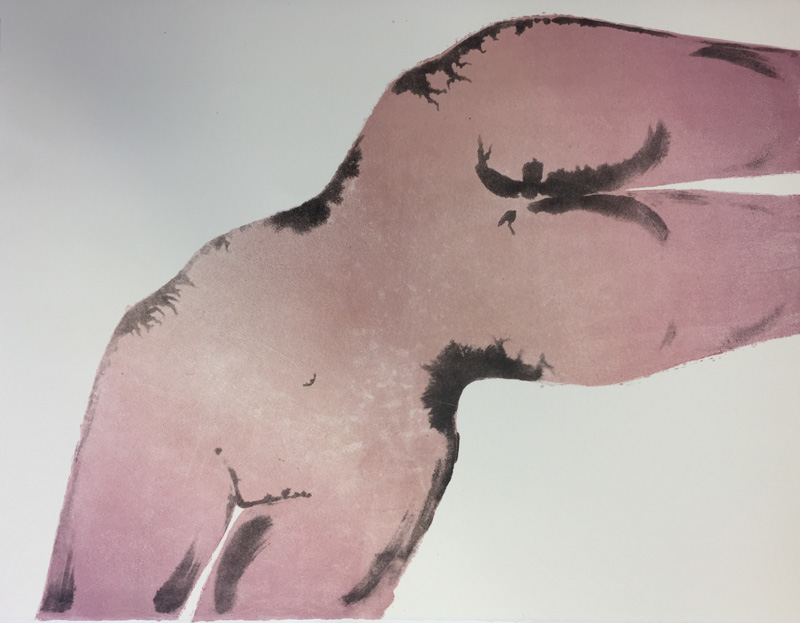

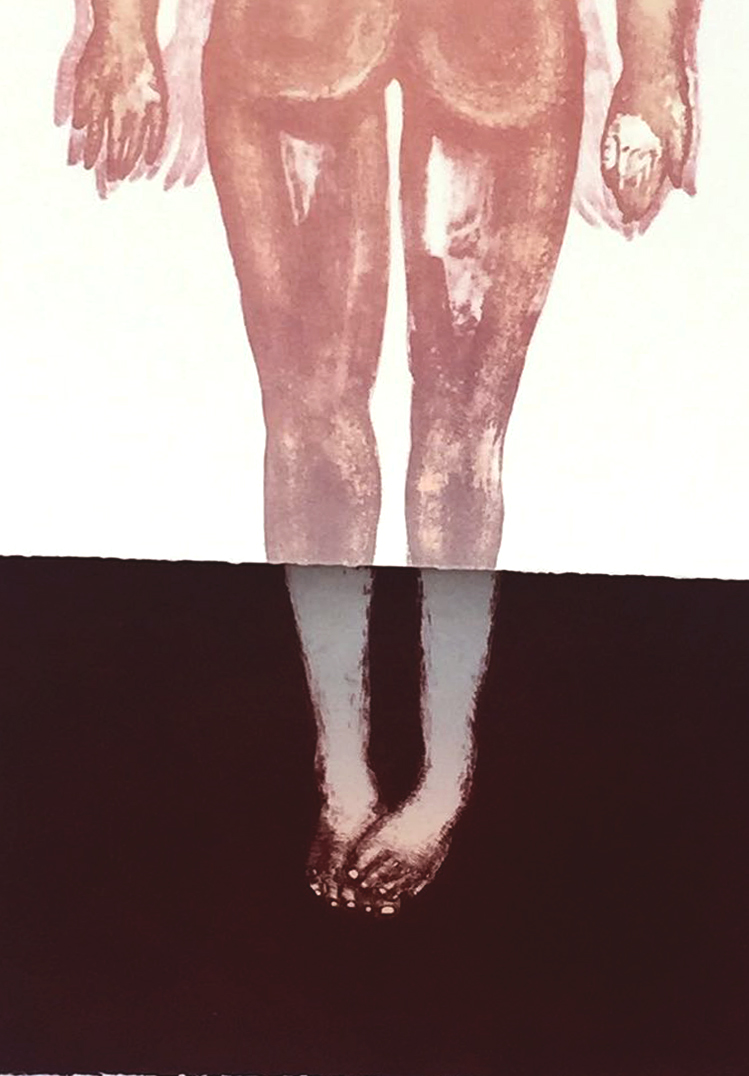

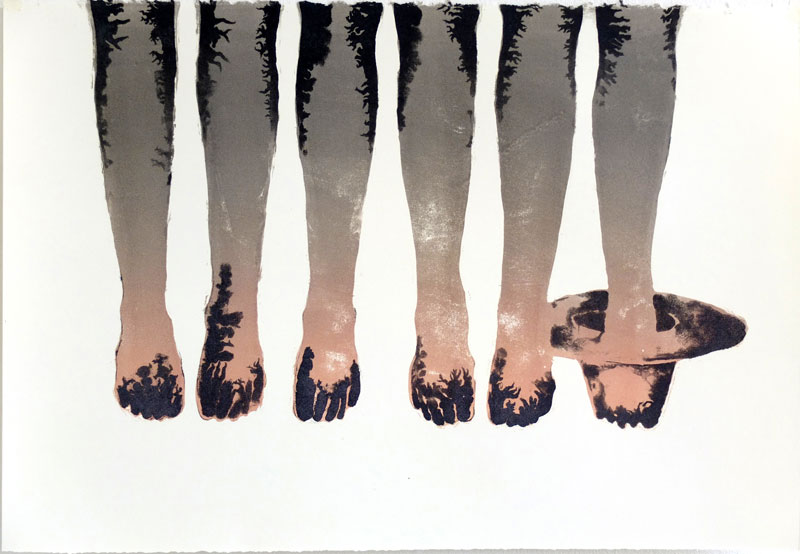

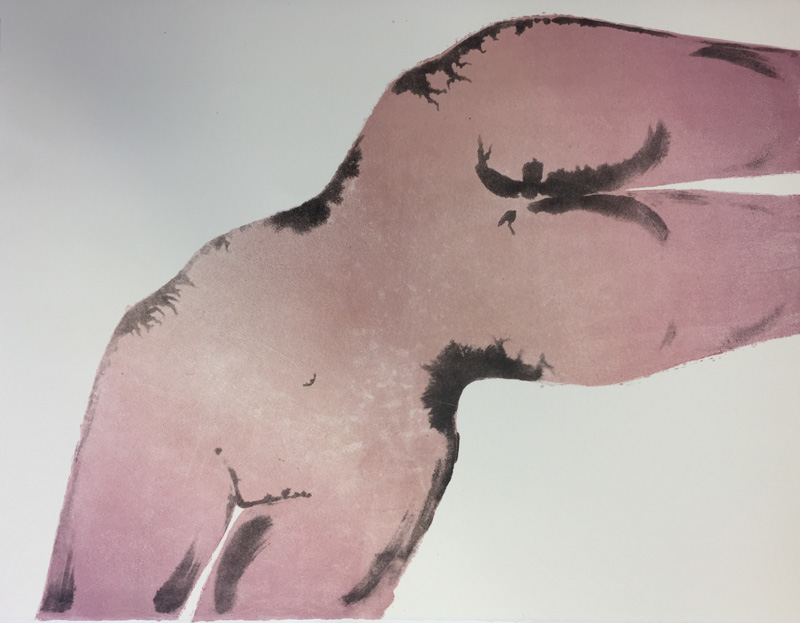

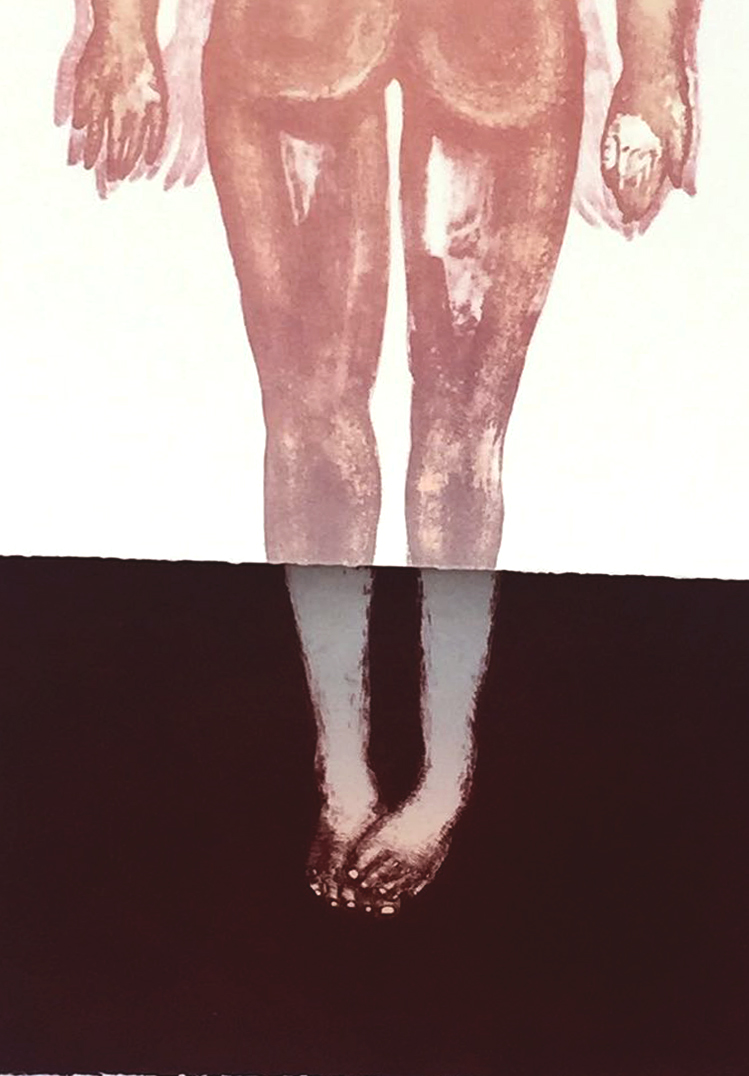

The style of emerging Chinese artist Kecheng Zhu’s portfolio of stone lithograph prints is unmistakeable. Not long ago completing an MA in Visual Art Printmaking at Camberwell College of Arts in London following her undergraduate studies at the Xian Academy of Fine Arts, Shanxi, in China, she has already carved out a strong artistic voice.

Overall, her work explores how body language reveals hidden truths and how unconscious body behaviours greatly affect our daily lives. Having lived and worked between cultures, Kecheng is also able to explore the different nuances of Eastern and Western body language through her art.

Among other exhibitions, Kecheng’s work has recently been on display with ArtChina at the Royal Academy of Arts during the 2018 London Original Printmaking Fair and will be included in our booth at Asian Art in London at the Design Centre Chelsea Harbour in November 2018.

Below, in her own words, Kecheng talks more about what she hopes to communicate through her work:

“Intertwined, touched, detached hands and feet speak about the relationships that I encounter in daily life, how conscious and unconscious bodily behaviours greatly affect our daily lives and affect how we really get to know a person, including ourselves. These specific human actions very much bring me into the sense of particular areas of bodies. It’s not a body as a whole, it’s a fragmentation.

Freud said: “He that has eyes to see and ears to hear may convince himself that no mortal can keep a secret. If his lips are silent, he chatters with his fingertips; betrayal oozes out of him at every pore.”

It seems only body language can tell the truth about people’s thoughts. The stability and level of tone do not make us distinguish between true and false. We are not polygraph instruments. Is he/she is shy? Is he/she pretending to be calm? Has he/she escaped something? Does the environment make him/her insecure? Whether we are close or not, a fingertip’s action, gives you insight.

We all have our own answers, and the importance of physical contact can not be ignored. Bones, organs, and Central Nervous System, our so-called command centre; these are all under our skin, but what is beyond the skin?

When we plan our actions, the brain gives clear instructions, but the subconscious may make the body react in advance. To me, the surface is a blurred boundary; I can’t clearly separated inside and outside. The figures that I create are based on my own reactions and the reactions of the people that I observe. The conscious and unconscious bodily reactions are the most important part in my works.

The different communication style between East and West also gives me inspiration. In my eyes, the way the East communicates with the West gives me different experiences and plays an important role in my observation.

All the prints are printed by stone lithographs. Feet and hands are the symbol I use all the time to represent the whole body. They became my own language. My own hands and feet will become the main actors to tell the story. I found my own symbols to explain the inside and outside.”

Visit the ArtChina booth at Asian Art in London at the Design Centre Chelsea Harbour, November 5-9 2018 to see Kecheng’s work. Art is available for sale. Please contact us for details.

《传统饾版研习》”紫竹斋“传统木版水印实践与理论方向研究生,二年级,学生:王豫敏,导师:王超.jpg)

《传统饾版研习》”紫竹斋“传统木版水印实践与理论方向研究生,二年级,学生:黄剑波,导师:王超.jpg)