One of the artists whose work we will showcase at the London Original Print Fair is Liu Jing. In our last blog post, he began to reflect on his ideas about art and printmaking after exhibiting in a solo show titled “Texture and Daily Life”, held earlier of this year in China. This is part two.

“My work doesn’t focus on trying to be traditional or contemporary. Tradition is good, contemporary is good too. If the work is neither traditional or contemporary, even better. Whats important is that I can live on what I like for many years; how lucky am I!

With my work, my only concern is that I want to do this and I like the way I’m doing things. I think it’s more interesting if I do something this way, that’s all. We know that traditional art today used to be contemporary art yesterday. All the cutting-edge and contemporary things today will become obsolete traditions sooner or later.

Does this have anything to do with me? Instead of worrying over these boring questions and trying to be a pioneer in the art world, I am more willing to get a block, take a knife, and easily sift a pile of sawdust. Or grind the stone, adjust some of the ink, and casually create some texture.

15,000 years ago, one afternoon in the southwest of France, the sun was warm with a gentle breeze. A content hunter who just had lunch woke up from snoozing. The prey in the cave behind him were enough for a few days and he was in a very good mood. Picking up a piece of brown soil from the ground, he painted a few wild horses on the stone wall in the cave to pass this long and boring afternoon. This is my imagination, but also a kind of art that I really love, and a leisurely style of art, although it is difficult to reach the state of real leisure and content!

My recent exhibition more or less revealed my dream, a kind of dream that printmaking gives me, and a refined ‘Daily Life’. In short, it is good to be a printer.”

Head back a post to read part 1 of Liu Jing’s comments on printmaking and be sure to visit us at stand 22 at the London Original Print Fair at the Royal Academy of Arts April 25-28, 2019 to see his work for yourself. If you’re interested in free or discounted tickets to the event, please contact us (available while supplies last).

One of the artists whose work we will showcase at the London Original Print Fair is Liu Jing. Below, he reflects on his ideas about art and printmaking after exhibiting in a solo show titled “Texture and Daily Life”, held earlier of this year in China.

“This is my 18th year of printmaking. This is what I have repeatedly told people recently. From the age of 18 to 36, I have devoted possibly the best of years in my life to printmaking. Please note that I am talking about printmaking, not art. In my case, printmaking is much more interesting and pure than art. I never have the idea of devotion to art, but I really believe that I can spend my whole life making prints. It’s not so important to do it better or the best in this field. Is there anything more interesting in the world than prints? In my opinion, no!

Many people asked me why I chose this unpopular art form back in my college days. In fact, it was because of the third year students who told me that ‘to study oil painting is very expensive; to learn Chinese painting you need high level of calligraphy skills’. So printmaking was the only option left.

One afternoon in my second year of university, I saw a book of ‘Chinese contemporary lithography’ in an antique bookstore in Er Fuzhuang, behind the college. I accidentally found one of my works was published in the book. Since then, I convinced myself that I was born for printmaking and no matter how difficult life has been, the situation has never changed.

Today, artists are generally afraid to limit themselves to a certain field. They are afraid that their identity is too specific and they are afraid of being conservative. Printmakers are also often afraid of being called printers, and always emphasise that they are artists. My ambition is not the same. I am eager to be able to embrace technical limitation and to make my work more authentic.

European and American artists were doing Dada off-canvas, ‘concept art’, breakthrough performances on the earth decades before us. As far as I can see, those artists have already settled down, calmed down, and let all art forms return to health, equality and order, with no more criticism and favouritism.

Every artist works on their own work, to have peace of mind. In English, the worker is called Artist; the printer is called Printmaker; and the very skilful technician is called Master Printer, which is extremely respectful of technology.

If you don’t have technique, you don’t have prints. If you don’t want to talk about technique, then don’t do prints.”

Come back next week for part 2 of Liu Jing’s comments on printmaking and be sure to visit us at stand 22 at the London Original Print Fair at the Royal Academy of Arts April 25-28, 2019 to see his work for yourself. If you’re interested in free or discounted tickets to the event, please contact us (available while supplies last).

As a cultural concept, “Asia” refers to a geographic space and as well as a historical and cultural identity. Asia was proposed as a community, actually a cultural oppression from Western centralism. In the past 100 years, “Western learning ” has eroded many regional primitive cultures, as well as forced another factor of culture into being: “Orientality”. The separation of Asia’s traditional values and the traditional cognitive structure from modern life, rapid migration of populations, and contemporary social consciousness, attracted people to the cultural ideals and identity, meanwhile neglecting the various cultural differences within Asia.

Literature and art have always been a mirror of thoughts, as has printmaking. Prints entered into China in the early 20th century with a strong impression of enlightenment, and then experienced the evolution of localisation and nationalisation. A contemporary printmaking scene was formed, which is different from the traditional or the Western printmaking scenes, accompanying the new round of Western contemporary art trends from the 1980s. Although the background and developments of printmaking in other Asian countries or regions varies, the traditional transformation based on the influence of Western learning and the inconsistent oriental efforts are self-evident and present sameness in time and appearance.

Anti-colonial discourse and cultural studies are not the only fresh topics to enter the art field in the early 1980s. Launched in 1987, the magazine “Third Text” has been devoted to discussing the colonial history of contemporary art and Eurocentrism; meanwhile, Singapore’s “New Asia Channel” has explored the cultural belonging and identity of Asia under the framework of a global social and political economy through the confirmation of “Asian values”…

Printmaking has a meaningful existence in the art world. Like a mixed-race child of the East and the West with strong cultural adaptability, printmaking should become a ground for nurturing Eastern and Western cultural communication. However, perhaps concerning “technical problems”, for many years the cultural attributes in the essence of printmaking have been obscured, which has led to the indifference of critics to the cultural appeals beyond technology in the practice of printmaking.

Through the research and display of representative contemporary printmaking in the Asian region, our exhibition aims to explore the reconstruction of Asian traditional cultural genes as well as the Asian subjectivity in the world cultural pattern dominated by Europe and the United States and encourage viewers to re-think how cultural identity is formed. In this exhibition, we also hope to use art to aggregate Asian countries’ thinking about the status quo of culture, to bridge the gaps caused by geographical restrictions by the artistic interaction, and to contribute to the development of Asian regional printmaking.

The development of modernisation in Asian countries is sequential; however, the root is always the traditional farming culture. The farming culture is based on the heavens and the earth, and advocates for the unity of nature. There are always a large number of Asian prints with the theme of natural objects where the artists puts forth his ideas and values. The objects speak and express emotion and, in the process of blending “things” and “I”, artists complete the spiritual journey of the natural interaction between the natural object and the self-subject. However, in the 20th century, industrialisation broke the traditional order of the cultivation of farming culture, separated the connection between man and nature, alienated people’s lives. This kind of alienation is reflected in printmaking, on the one hand, the vigilance and anxiety about the unknowable industrial future, and on the other hand, the attachment and obsession with the natural and spiritual space. Such creating method of “things” and “I” are also important manifestations of “Orientality” in Asian prints.

Article originally published by the Printmaking department of Sichuan Fine Art University, China

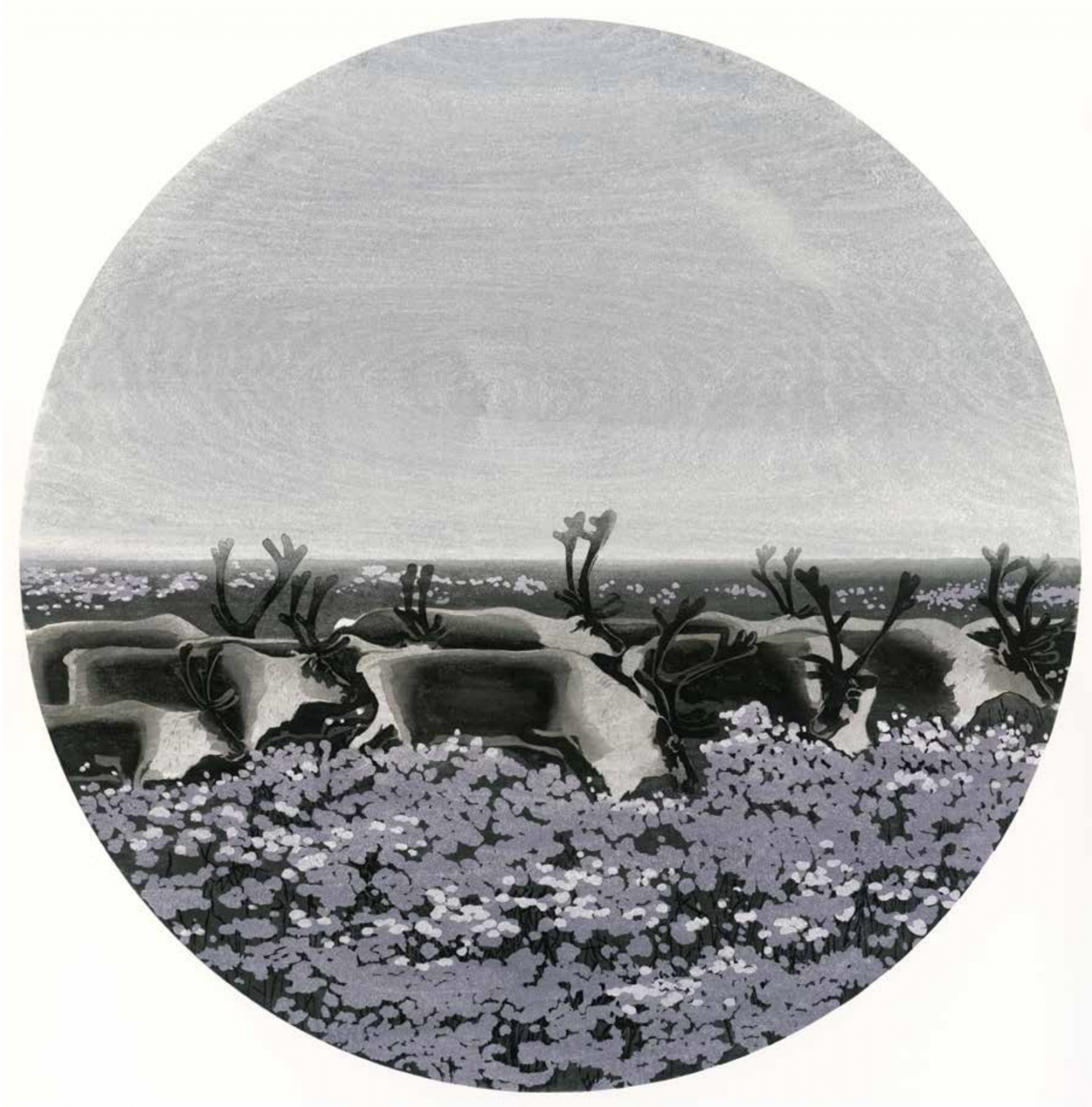

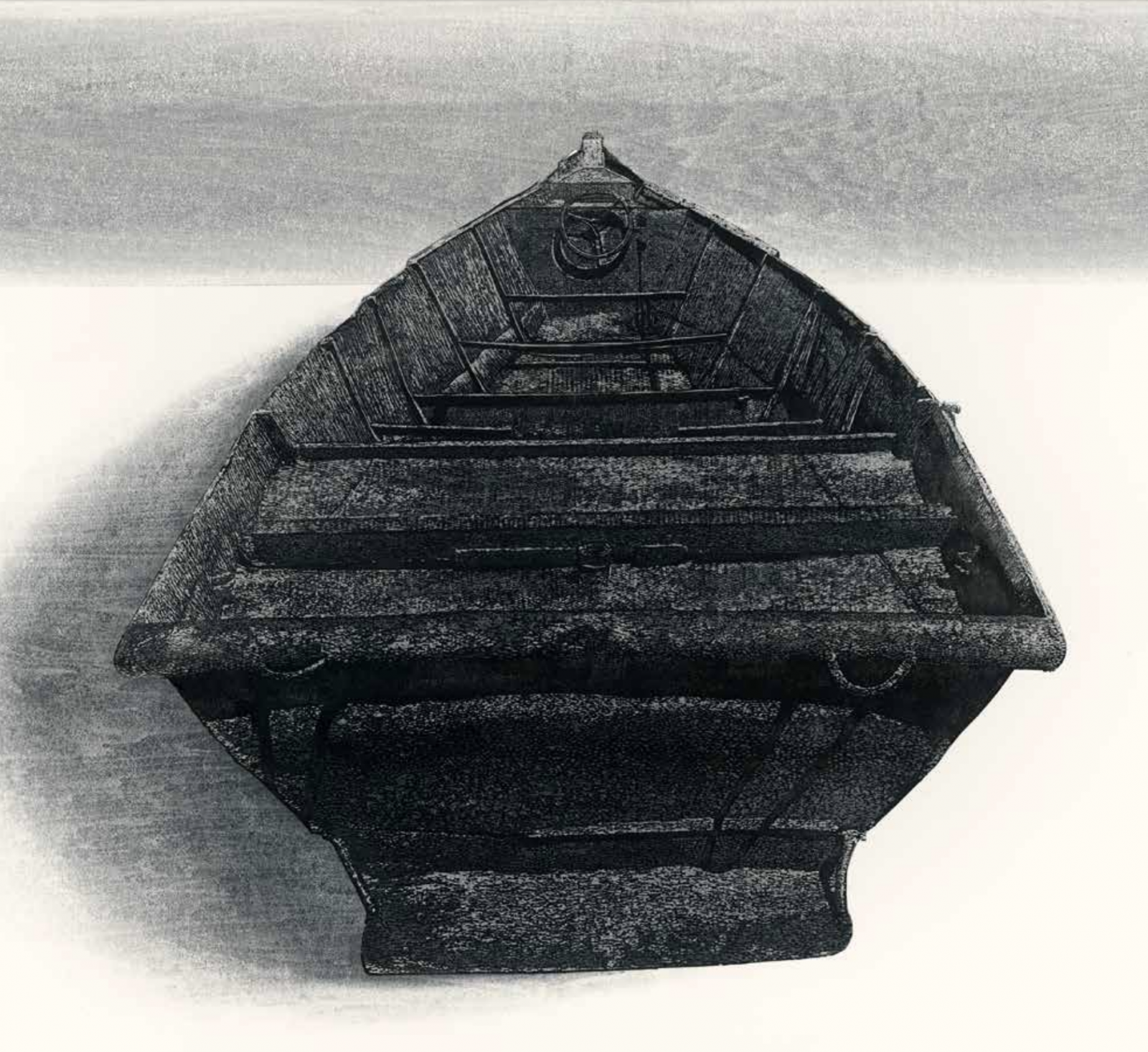

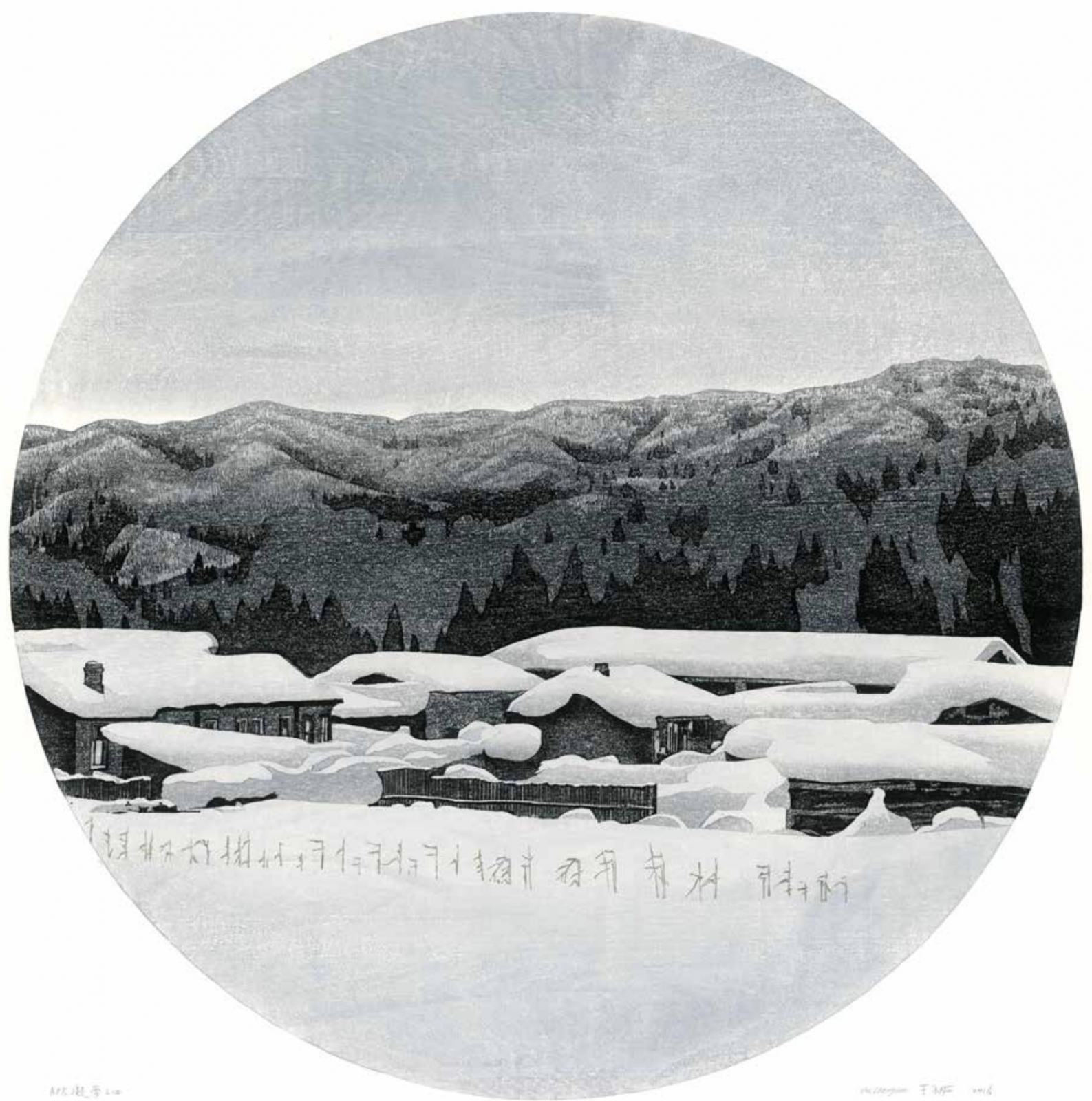

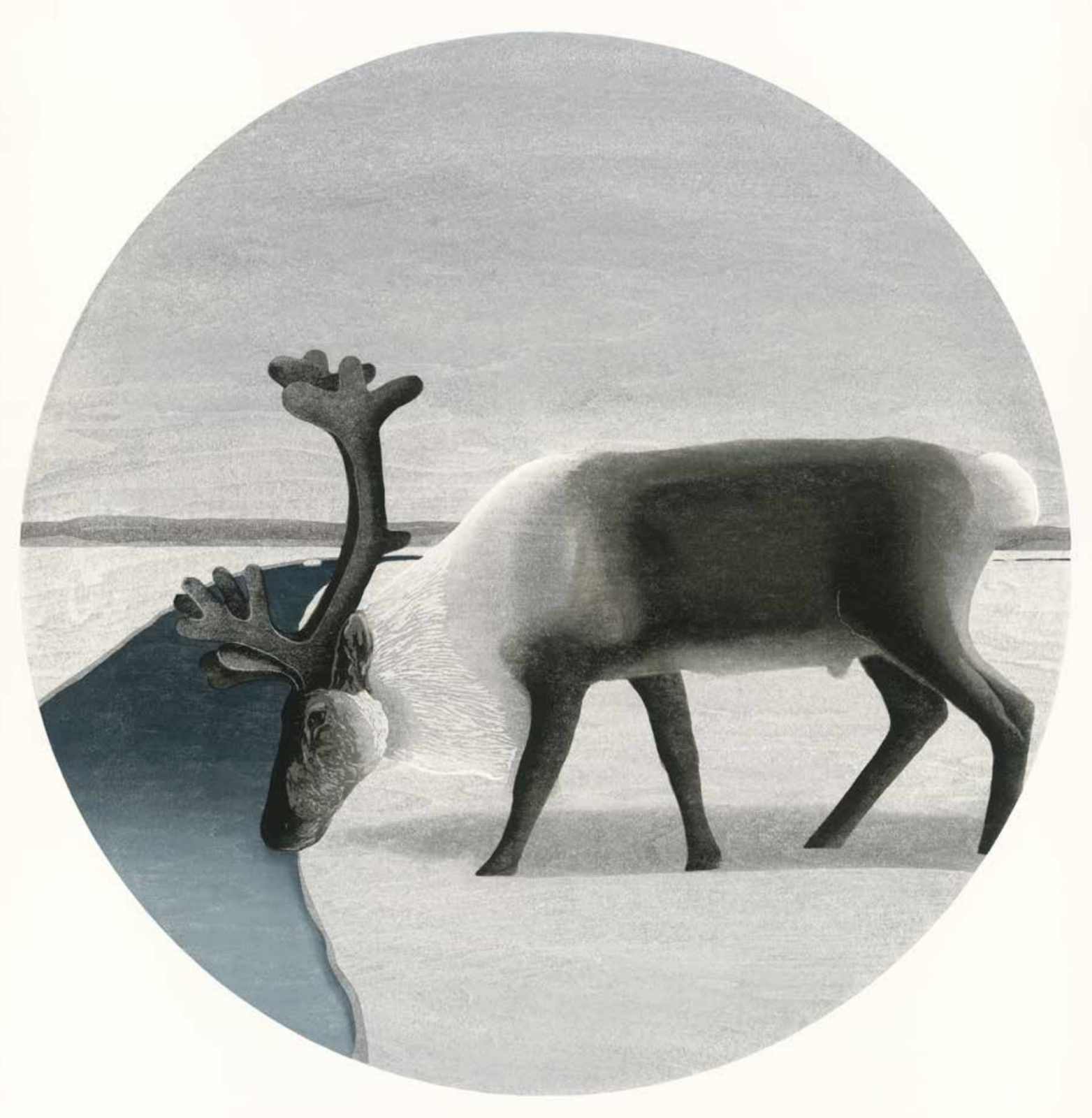

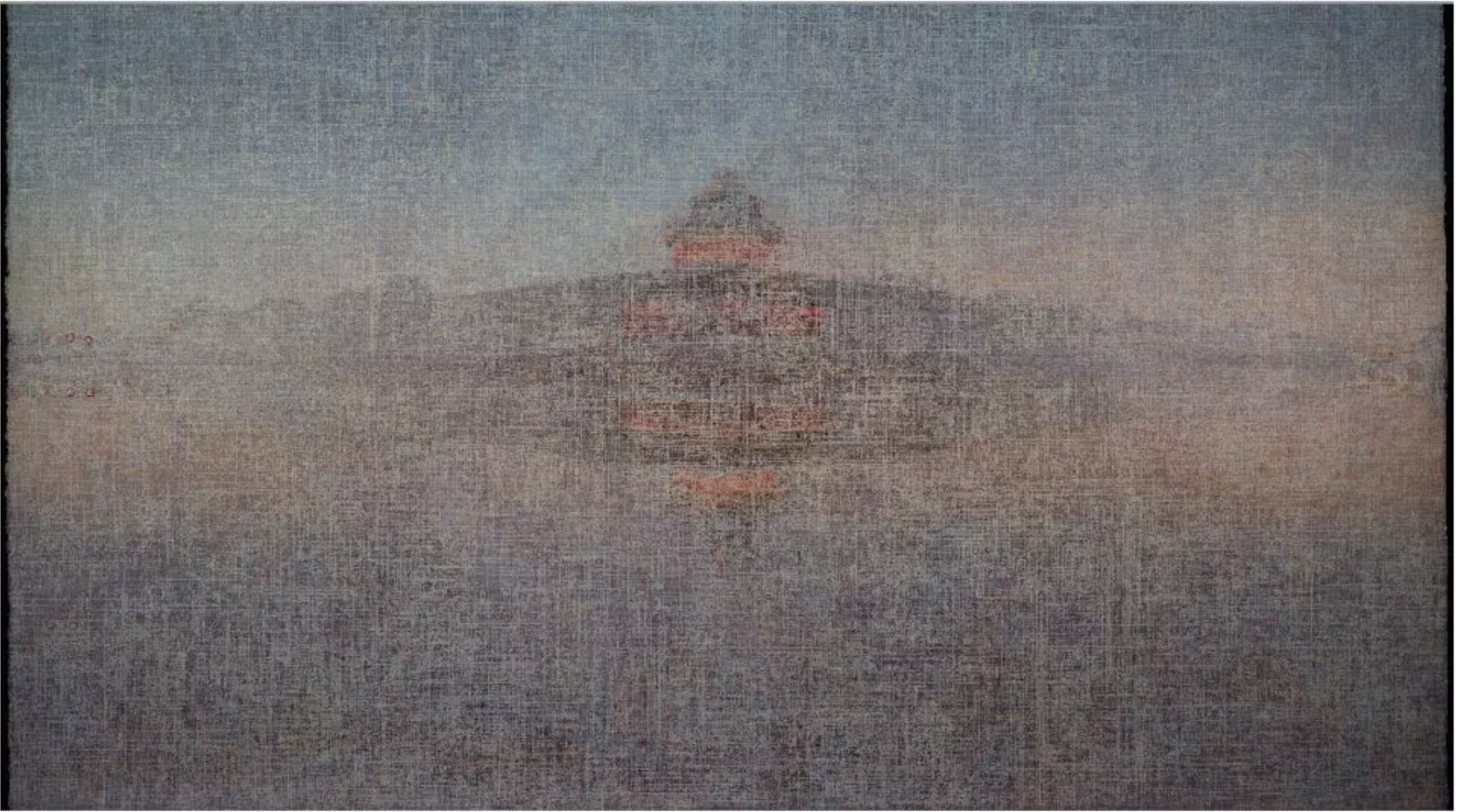

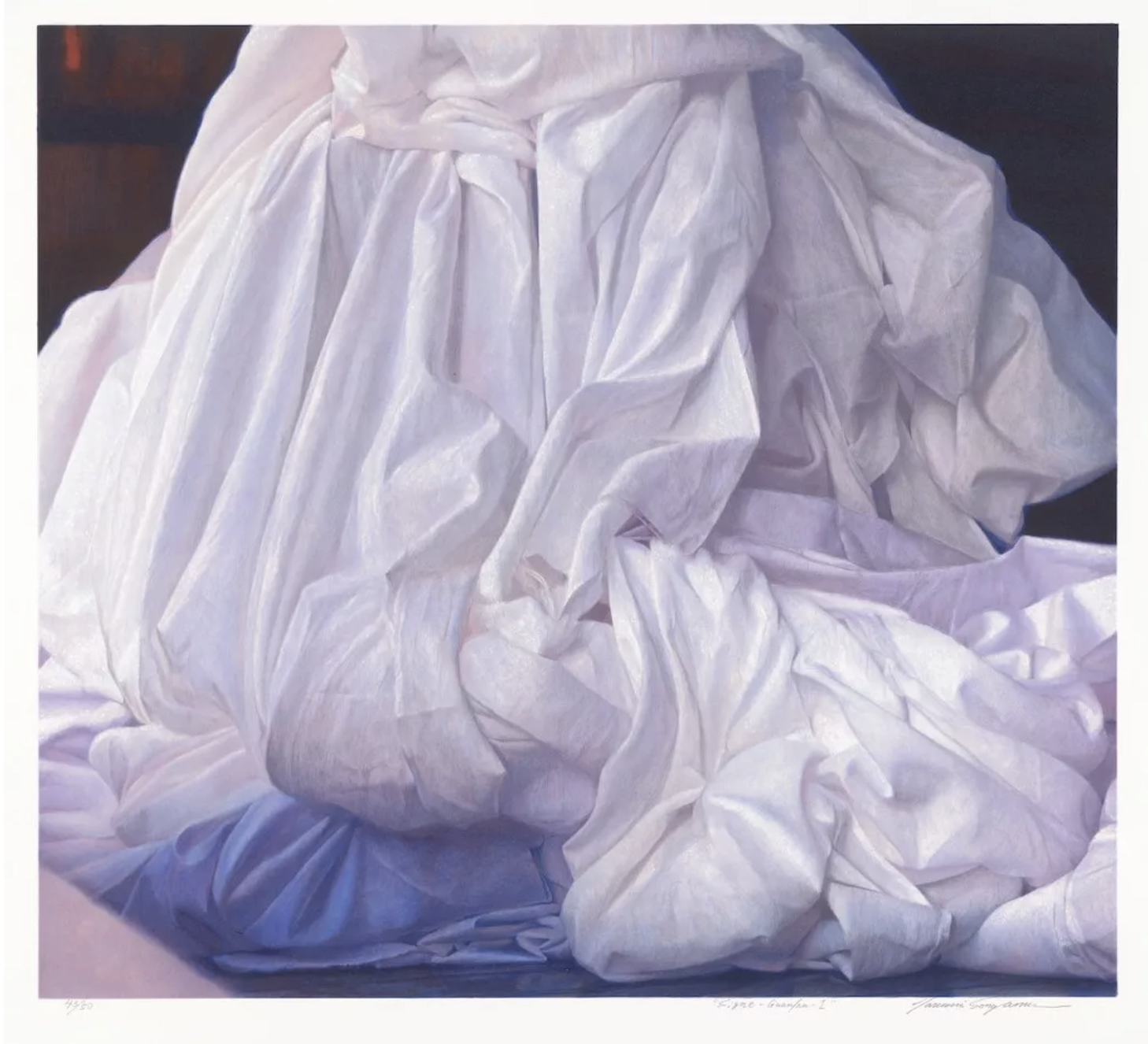

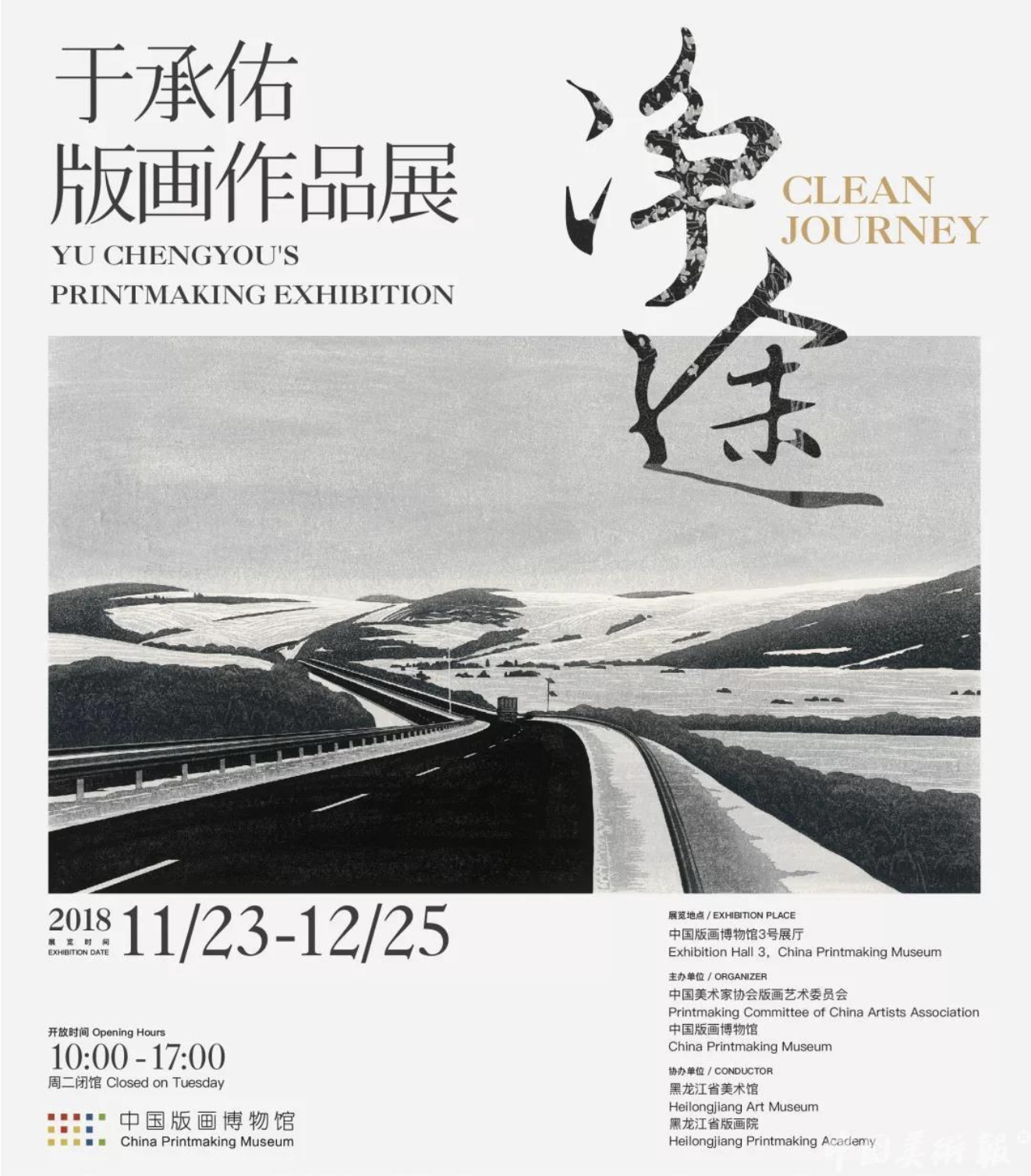

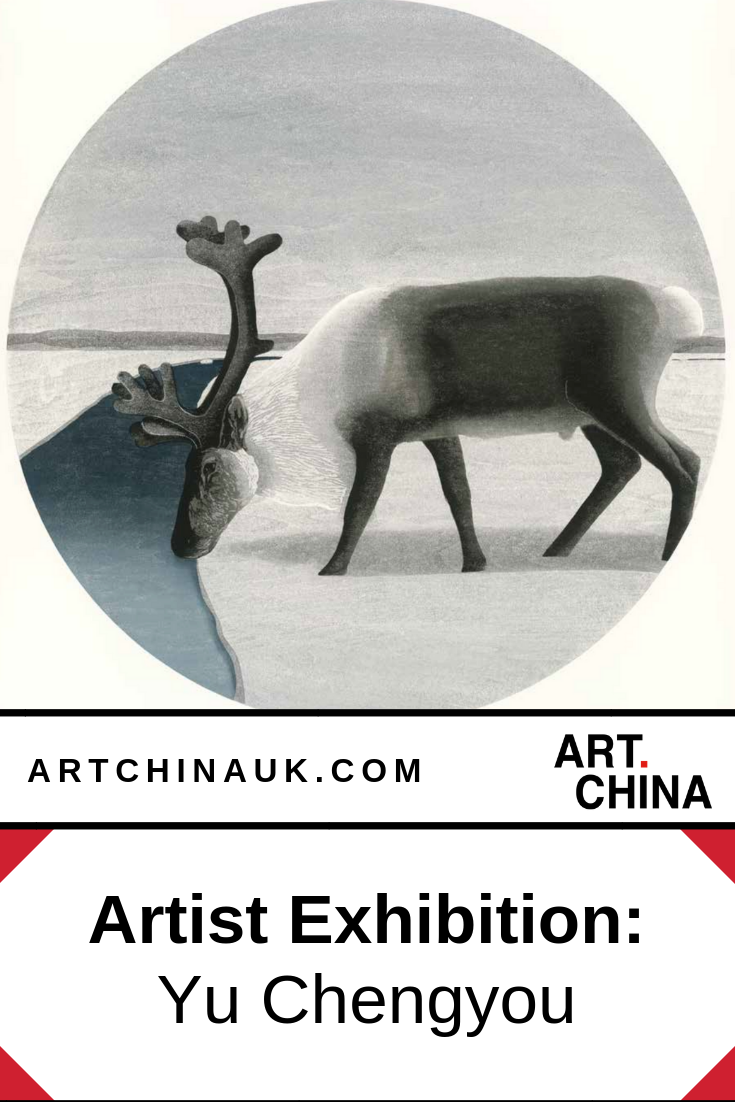

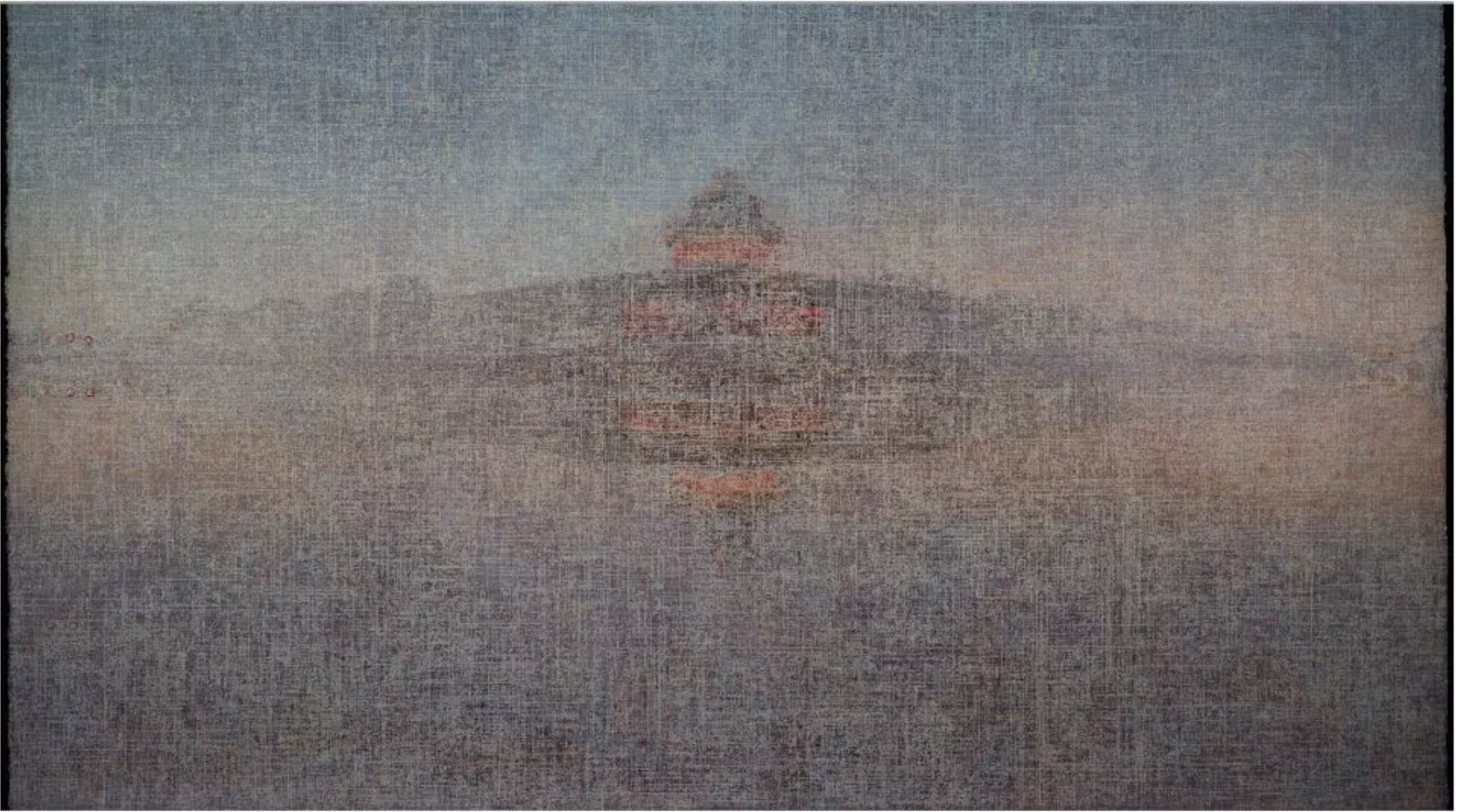

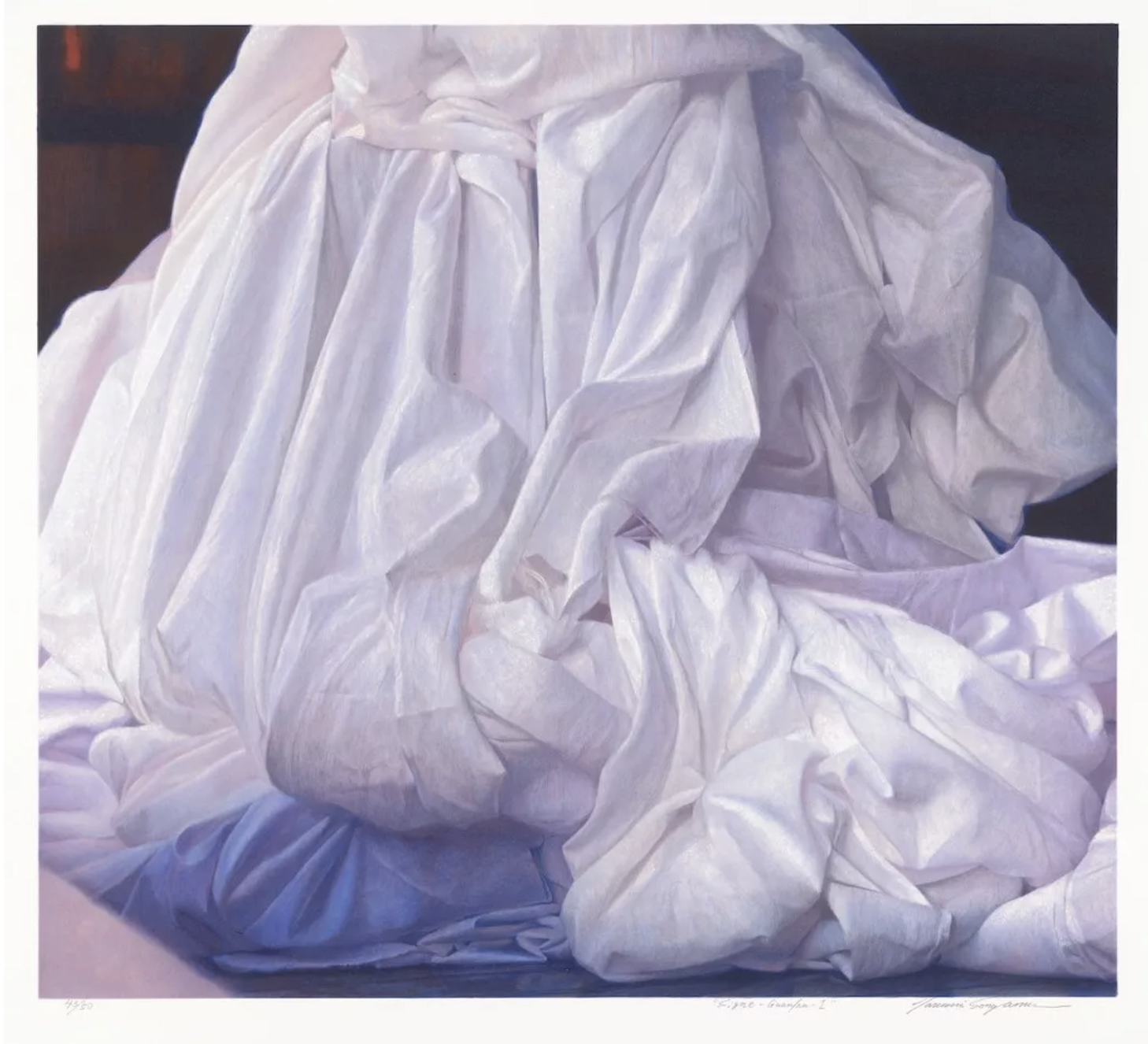

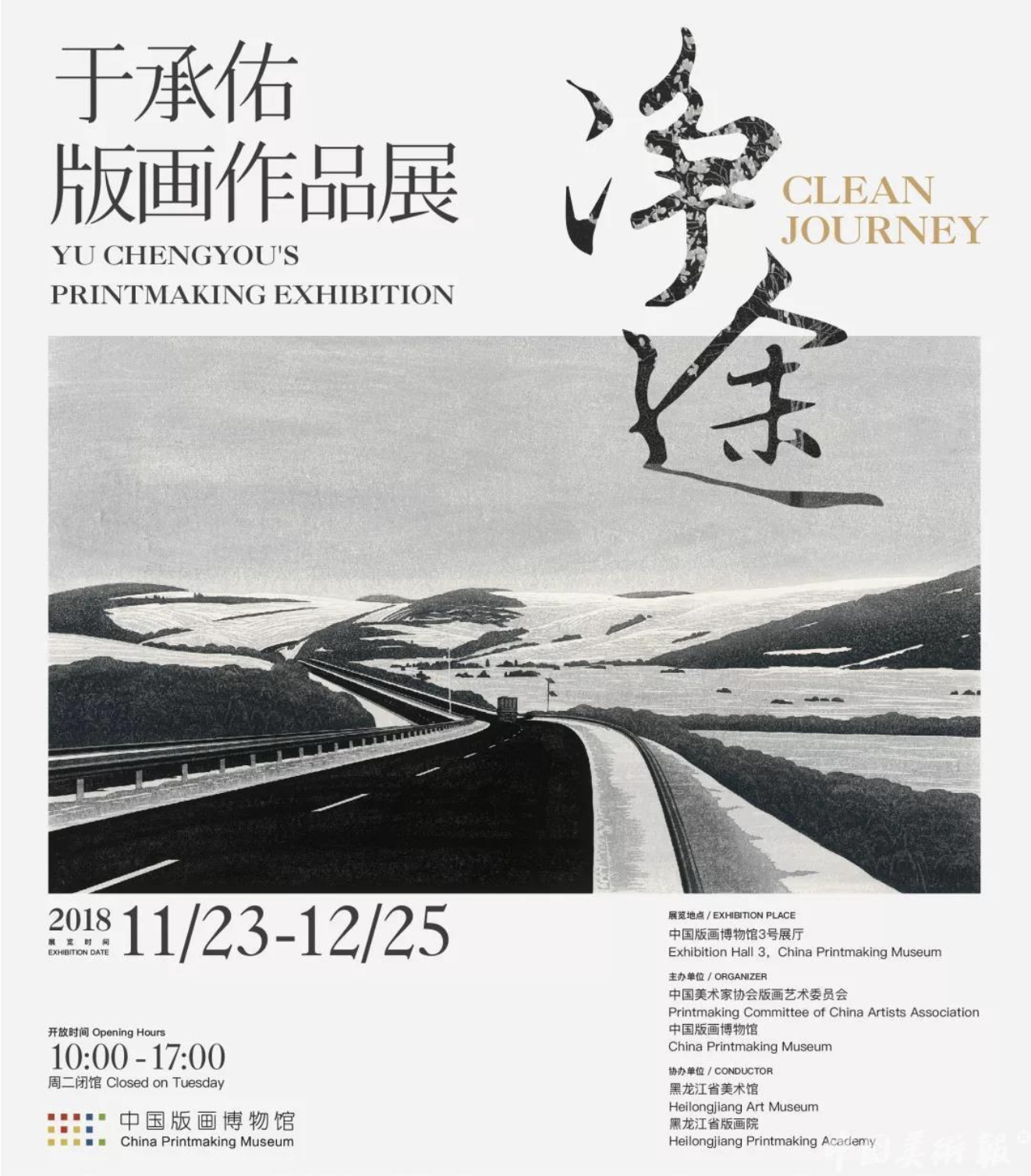

One of our talented Chinese artists, Yu Chengyou’s images draw upon natural surroundings, from wildlife to human life, places that, through the simplicity of his style, seem tranquil and uncluttered. His prints offer quite a contrast to the metropolises’ of China; they depict places that bring solace from the maddening crowds and industrialisation of China today. His work promises something better for us, a calmer world to strive for.

We’re pleased to share a few images from his solo printmaking exhibition titled “Clean Journey” that was shown at the end of 2018in Shenzhen, China. Below are the images from the exhibition catalogue and a few words from the artist himself, talking about his artistic journey.

My Artistic Journey:

I was born in the rural area of Shandong, China. My father had participated in the local army during the Second World War against Japan. Later, I learned that such a unit was called an “armed force.” My father has always been a cadre in the village. During the Great Leap Forward in 1958, the village was already starved to death. He was afraid of taking responsibility and left his hometown to come to Heilongjiang Coal Mine. For this reason, he was identified as a “Out Party Member” during the Culture Revolution. My mother gave birth to me when she was 40. When I was seven years old, I went to the mine with my mother to reunite with my father.

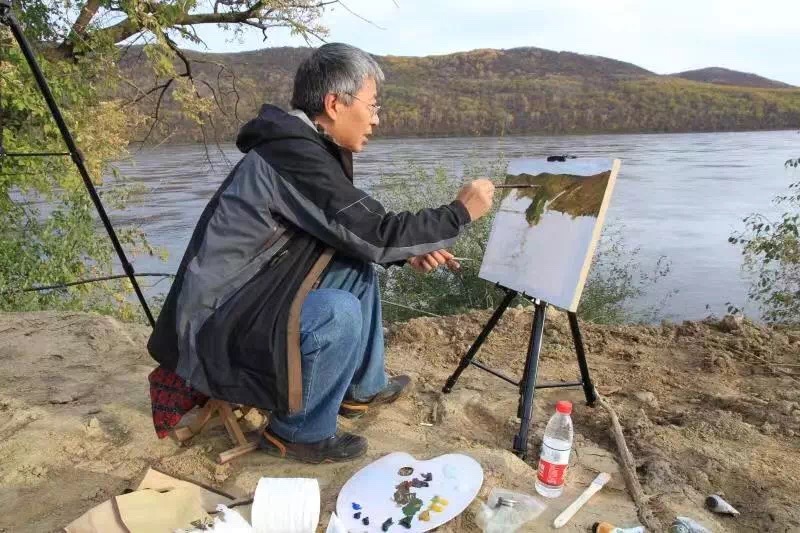

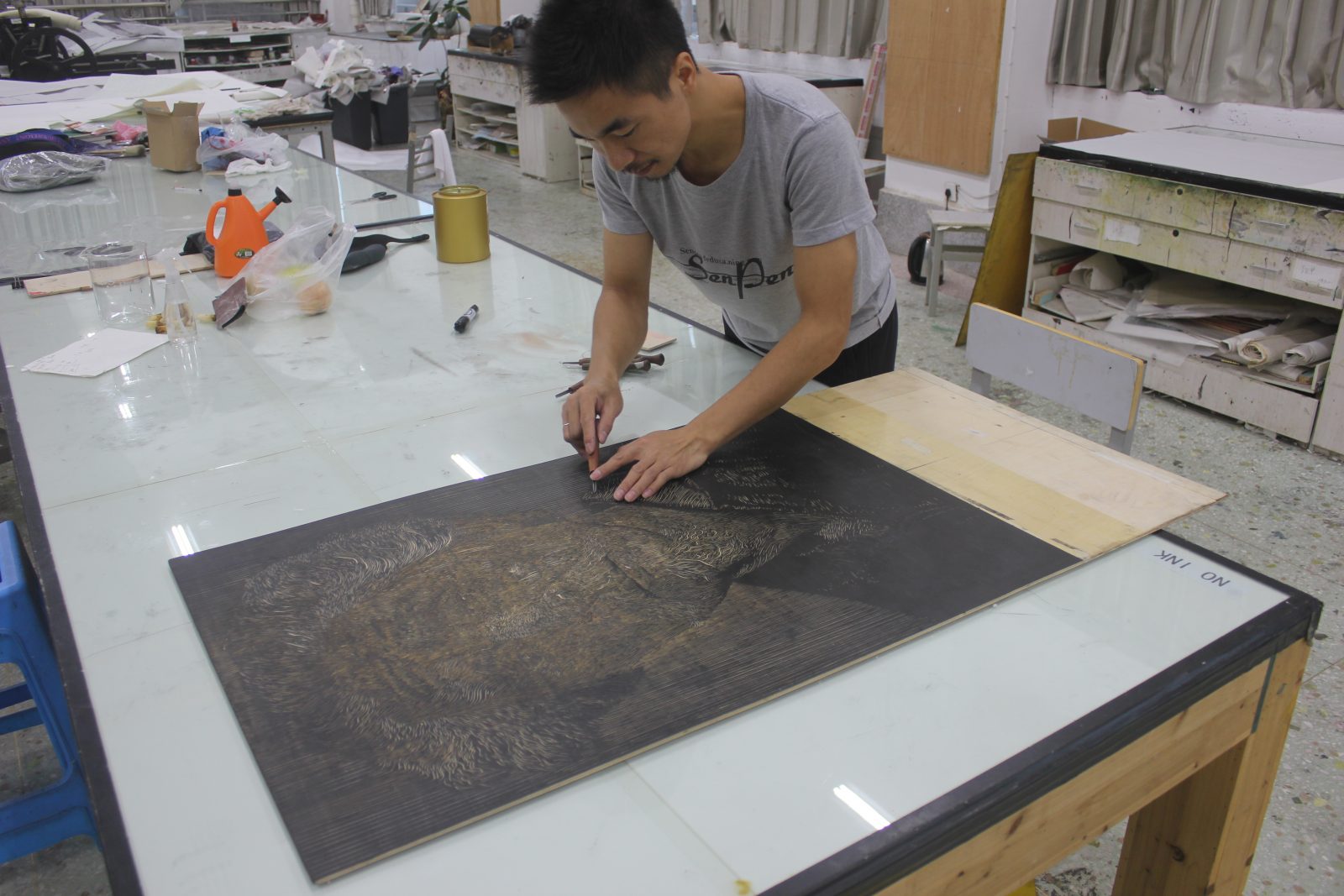

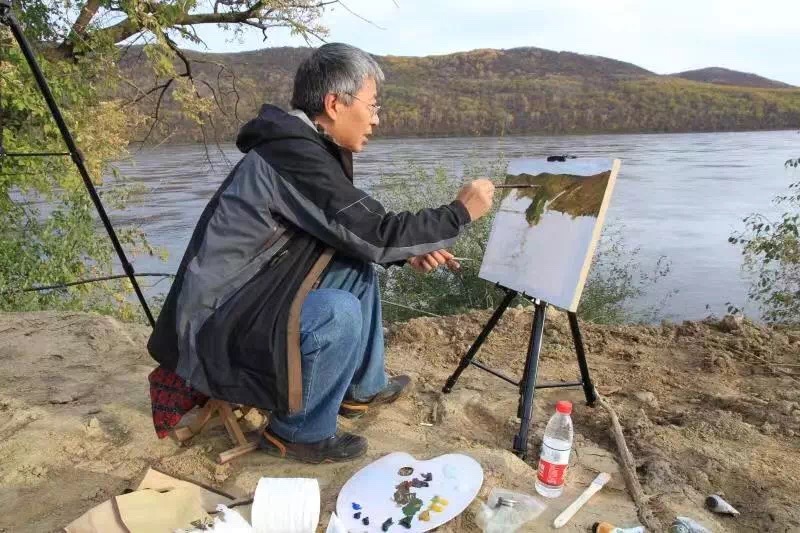

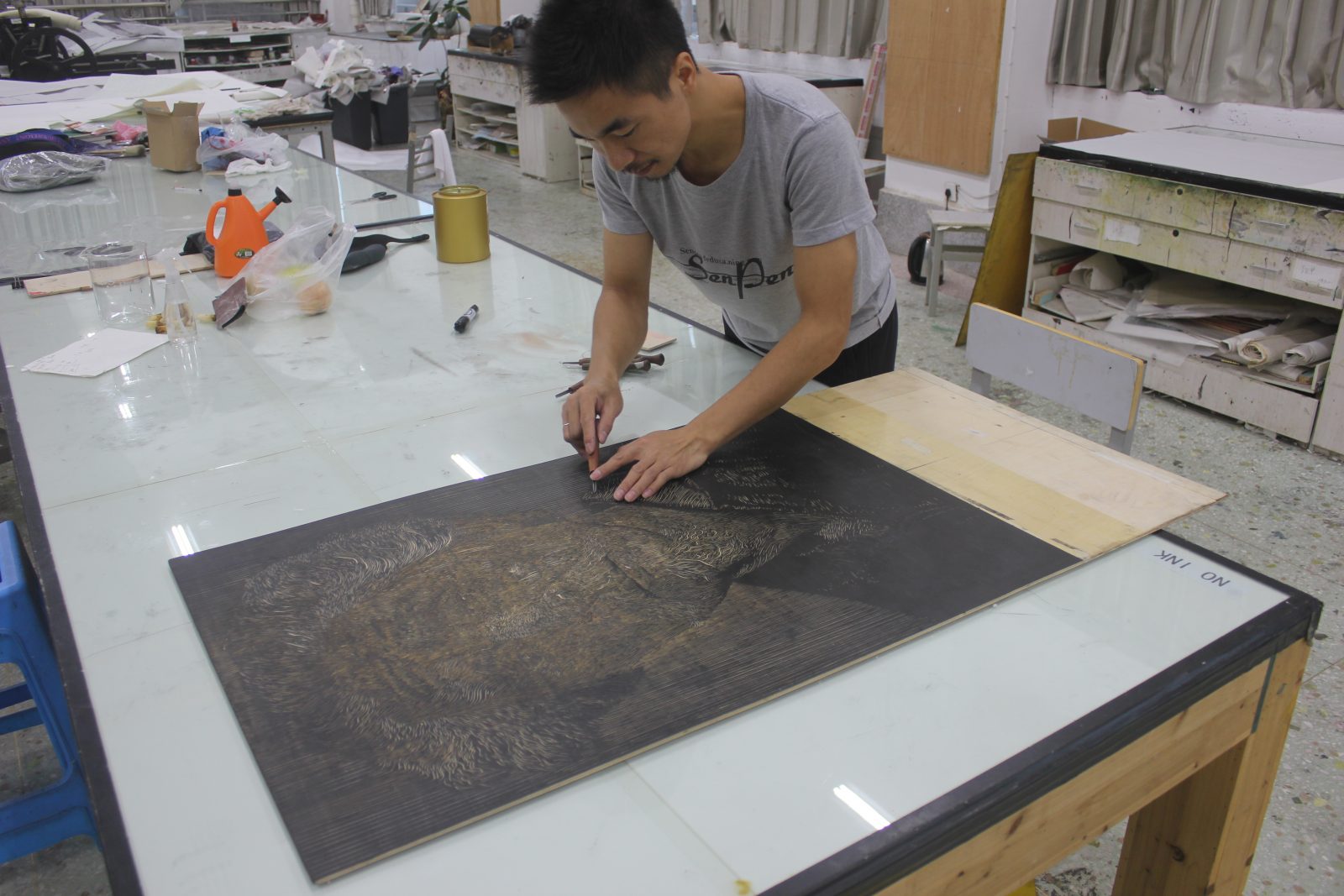

Photo: Yu Chengyou was in Guanlan Printmaking Centre at ShenZhen

Photo: Yu Chengyou was in Guanlan Printmaking Centre at ShenZhen

Although my father didn’t have higher education, he had beautiful handwriting. My mother painted and did various embroideries. She also specialised in the traditional moulding by using Shandong flavours. I later learned that this kind of craft is called “flavouring moulding.” If I have a little talent for painting, maybe it was inherited from my parents.

When I graduated from high school in 1969, I got caught up in the movement which called on graduates to go to China’s countryside to work. I went to the Great Northern Wilderness (in Northeast China), which was thousands of miles away from home. Since I was a child, I liked drawing. After I went to the countryside, I started drawing with some older educated youth who came from some of the big cities. At that time, we were very hardworking. After work, we sketched and draw portraits. In 1973, because of my interest in drawing, I became an art teacher in the army. In this way, there was no need to work early in the field in the morning, and there was plenty of time to draw. In 1977, I was transferred from the regiment to the division and had the opportunity to draw together with some of the educated young artists, such as Hou Guoliang and Lu Jingren. I learned a lot from them, and practiced everything from sketches to oil paintings to comics.I rapidly improved my artistic skills. Later, Hou Guoliang and Lu Jingren left the district, and I transferred to the division club and became a full-time art worker.

Later, I participated in the Jiamusi Agricultural Reclamation Bureau and took a printmaking class tutored by Mr. Hao Boyi; that was the beginning of my focus on printmaking.

I stayed in the Great Northern Wilderness for 18 years. At that time, I was very naive. I didn’t want anything besides the time to focus on my art. Now that I think about it, I really appreciated that period whenI worked hard to learn how to make art.

More than 30 years have passed, and I have always loved printmaking; the experience of this is only known to myself.

I have always believed that art is inseparable from life. I have traveled all over Heilongjiang in these years and I go to countryside two or three times a year to experience quieter life and collect materials. Every time, I gain a lot; in addition to accumulating a lot of creative materials, I also let my body and mind wander into nature, to help me to maintain a peaceful, simple state.

My requirements for my own creativity and works are not high, but I approach it as seriously and sincerely as possible. I don’t like bluffing, and so it is the same in my work.

In recent years, I have seen some works that have awed me and some that have confused me. I always feel that I am out of date, but I have an open-minded attitude. Printmaking is my speciality and I am continuing to work in this field. I will keep going, step by step…

Read more about Yu Chengyou and see the prints we have for sale from this artist on the ArtChina UK website.

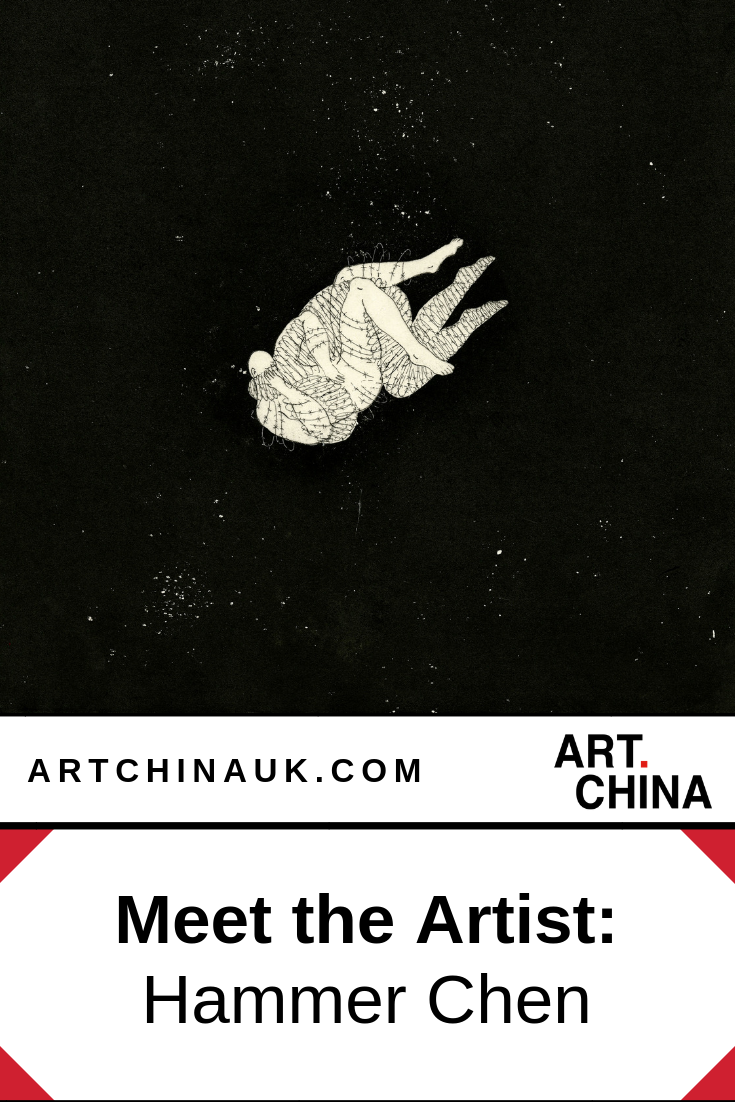

One of the talented emerging Chinese artists we’ll be exhibiting at November’s Asian Art in London show is Hammer Chen, whose creative life bounces between Shanghai and London. Hammer is a printmaker, an artist and illustrator whose work, as she puts it, stems from an interest in using marks and textures to express sensations and emotions. Since 2013, she has had several exhibitions in London and, in 2016, graduated with an MA in Illustration from Camberwell College of Arts. She won the Gwen May Award from the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers (RE) in 2016 as well and was selected to be a member artist of the RE in the same year.

From 2016, Hammer began to run a printmaking art studio called Wait and Roll in Shanghai in an effort to increase access to printmaking in China. Services of her studio include printmaking workshops, printmaking publication, print service, open space and an artist residency. The photos throughout this post were all taken at Wait and Roll.

Hammer’s series of prints that we’ll have on display in the ArtChina booth at Asian Art in London is from her degree project.They’re much darker than the work in the images here, and run deep into the psychology of being. They revolve around the topic of Maladaptive Daydreaming, which she defines in our interview below. Read on to find out more.

ARTCHINA UK: Tell us about the work you made for your MA project.

HAMMER CHEN: My subject is Maladaptive Daydreaming. “Maladaptive daydreaming is a psychological concept to describe an extensive fantasy activity that replaces human interaction and interferes with academic, interpersonal, or vocational functioning.” So the series of works is exploring fantasy, struggle, disconnect between mind, body and self.

ARTCHINA UK: What inspired you to make your final piece?

HAMMER CHEN: The main reason that I chose the subject is that I realised I’ve developed Maladaptive Daydreaming in the last two years and therefore felt the need to explore this in my work. Also, I realised lots of people are suffering from this but they don’t want to share the bad experience of daydreaming because they are afraid of incomprehension. I do feel it’s necessary to let people know that this problem exists and we should pay attention to it.

ARTCHINA UK: How did you start this project? If you’d like you can make it as a step by step explanation.

HAMMER CHEN: I recalled a lot my previous experience to begin the sketches. It was hard in the beginning, but after I started to open myself up and express my real feelings, it became a process of self-curing. I made many sketches before I began etching. Even while I was in the etching stage, I still kept doing sketches. I picked the ideas which are most expressive then made them into etching pieces.

ARTCHINA UK: What technique did you choose to make your final piece and why?

HAMMER CHEN: I chose to do etching for the final project. Before I started printmaking, my works went through several different stages. They pretty much all stemmed from my interest in making marks and textures.The reason I am so keen on working with textures is that they can give an image a strong atmosphere, provide a different quality and build space for sensations and for the imagination to run wild. When I got into the printmaking studio, I realised that this is an ideal way to produce works with great quality which, at same time, can still be narrative.

ARTCHINA UK: Tell us about any difficulties or challenges you found while making your final piece.

HAMMER CHEN: The challenge might be the uncertainty of the final results and the long process. Sometimes you won’t know what is going to happen on your plate until the last minutes before you see the prints. But actually, I really enjoyed the waiting and appreciated all the failures and surprises that happened in my works throughout the process.

To see Hammer’s work in person, visit the ArtChina booth at the upcoming Asian Art in London exhibition or the Woolwich Contemporary Art Fair, both in November 2018, where we will have her prints on display and for sale.

Photo: Yu Chengyou was in Guanlan Printmaking Centre at ShenZhen

Photo: Yu Chengyou was in Guanlan Printmaking Centre at ShenZhen